INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use poses a serious threat to public health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it causes over 8 million deaths globally each year1. For this reason, tobacco control has been established as a specific target within the Sustainable Development Goals – specifically Goal 3, ‘Good health and well-being’ – and is considered a global development priority2. Although the global smoking rate among people aged over 15 years declined from 22.7% in 2007 to 17.5% in 2019, according to recent WHO reports, it remains a significant concern3. In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), 70% of smokers begin smoking before the age of 18 years4. This is particularly relevant in adolescents, who are more vulnerable to peer pressure and experimentation, and for whom early tobacco use can impair lung growth and brain development, increase susceptibility to respiratory diseases and reduce physical performance and endurance5,6. This underscores the need for effective prevention strategies.

Several studies have identified factors associated with cigarette use7-9. Psychological risk factors include depression, anxiety, poor academic performance, feelings of rejection, and underdeveloped social skills7. At the family level, risk factors include low emotional attachment, overprotective or rigid parenting, and poor communication7. Parental absence, limited involvement in family decisions, and frequent conflict have also been implicated9. The family environment is therefore critical to early smoking initiation7-9. Empirical evidence from the region supports these mechanisms. A study in Chile found that adolescents exposed to smokers at home were up to 70% more likely to experiment with tobacco8, while, in Cuba, those with family members who smoke were about twice as likely to have ever smoked10. This vulnerability is further amplified in permissive households, where low risk perception and the normalization of smoking promote earlier tobacco experimentation11. Given that youth smoking remains a persistent public health problem, with rates reaching up to 20% in some countries in the region, further research and evidence-informed approaches that consider the family unit are needed to guide future prevention efforts12.

Consistent with these regional findings, global evidence also highlights the strong influence of household smoking behavior on adolescent tobacco consumption. A meta-analysis of 58 studies confirmed that parental and sibling smoking significantly increase the risk of smoking uptake among adolescents13. Despite this, there is limited evidence exploring the association between exposure to tobacco smoke at home and smoking intentions among never-smoking adolescents in LAC. The Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS)14 applied in several countries across the region, offers data on household exposure and smoking intentions in adolescents, creating an opportunity to examine this association in greater depth. The GYTS is a school-based survey with an internationally standardized methodology targeting adolescents aged 13–15 years, with the objective of monitoring tobacco use and assessing related attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors14.

This study aims to examine the association between exposure to tobacco smoke at home and the intention to smoke among never-smoking adolescents in LAC. We aim to understand how the family environment shapes perceptions and attitudes toward tobacco use in this vulnerable population. The findings may contribute to the existing evidence base and support future efforts to design context-appropriate strategies to prevent early tobacco initiation and its long-term health consequences.

METHODS

Study design and data source

We conducted an observational, analytical, cross-sectional study based on a secondary analysis of data from the GYTS, collected between 2013 and 2021, in countries across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC)14.

The survey uses probability sampling for nationally representative estimates by sex with a minimum of 1500 students from at least 20 schools per country15. It employs a geographically clustered multistage sampling design15. The survey used a two-stage sampling strategy. First, schools were selected with probability proportional to enrolment size15. Second, classes within those schools were randomly selected15.

We included the most recent surveys from Latin American and Caribbean countries that had collected the variables of interest. The selection comprised data from Antigua and Barbuda (2017), Argentina (2018), Bahamas (2013), Barbados (2013), Belize (2014), Bolivia (2018), Costa Rica (2013), Cuba (2018), Ecuador (2016), El Salvador (2021), Grenada (2016), Guatemala (2015), Guyana (2015), Honduras (2016), Nicaragua (2019), Panama (2017), Paraguay (2019), Peru (2019), Dominican Republic (2016), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (2018), Saint Lucia (2017), Suriname (2016), Trinidad and Tobago (2017), Uruguay (2019), Venezuela (2019), and five regions of Chile: Arica and Parinacota (2016), Biobío (2016), Metropolitana (2016), Tarapacá (2016), and Valparaíso (2016)14.

We included adolescents aged 13–15 years, as this is the target population of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey14. The final analytical sample consisted of adolescents from LAC countries who had never smoked.

Participants

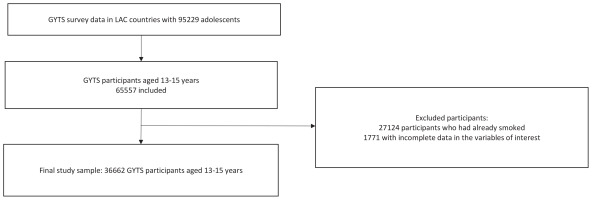

The Global Youth Tobacco Survey included all secondary students present in the selected classrooms who provided informed consent14. After applying the eligibility criteria and excluding records with missing data on key variables, the final analytical sample comprised 36662 adolescents from 27 Latin American and Caribbean countries (Figure 1).

Data collection

Data were collected using self-administered questionnaires with optical mark recognition forms designed for the GYTS, enabling later scanning and processing. Sample substitutions were not permitted to preserve representativeness and avoid bias. The GYTS recommends administering the survey in the first half of the academic year, preferably mid-morning, and avoiding exams and lunch hours to maximize participation15.

Variables

Dependent variable

Smoking intention was defined as an adolescent’s willingness, or desire to smoke in the future. This variable was derived from the question: ‘Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “I think I might enjoy smoking a cigarette”?. Response options were: strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree. For the analysis, responses were dichotomized. The variable was coded as ‘yes’ if the adolescent answered ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’, and ‘no’ if they answered ‘disagree’, or ‘strongly disagree’.

Independent variable

Household exposure to tobacco smoke was defined as the presence of tobacco smoke inside the home due to smoking by other household members. This variable was based on the question: ‘During the past 7 days, how many days has someone smoked inside your home, in your presence?’. For the analysis, the variable was dichotomized. It was coded as ‘no’ if the adolescent reported 0 days of exposure in the past week, and as ‘yes’ if exposure occurred on at least one day.

Covariates

Sociodemographic variables were included to assess potential confounding of the association between household tobacco smoke exposure and smoking intention. These variables were sex (male or female) and age (13, 14, or 15 years).

Data management and statistical analysis

We downloaded data from the Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) Microdata Repository of the World Health Organization. Before merging the datasets, we verified that each file contained the relevant variables for analysis, including sample design variables (weight, stratum, and primary sampling unit). Once verified, we merged the datasets using the append command in Stata.

We conducted statistical analyses using Stata version 18.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and generated forest plots in RStudio (R Core Team, 2022). To account for the complex sampling design, we used the svy command for representative estimates. We created unique identifiers by combining country codes with primary sampling units and strata to preserve the sample design structure. Jamaica was excluded from association analyses due to having only one sampling unit and stratum, which resulted in zero design degrees of freedom and prevented standard error and confidence interval estimation. It was only retained for country-specific exposure and outcome estimates.

General characteristics were described using absolute and relative frequencies, weighted by country. The chi-squared test with Rao-Scott correction was used to assess bivariate associations between household exposure to tobacco smoke, covariates, and smoking intention. To further examine this association between household exposure to tobacco smoke and smoking intention, we used multivariable generalized linear models with a Poisson distribution and a log link function, adjusting for sex and age. We estimated adjusted prevalence ratios (APR), with statistical significance set at p<0.05. We calculated APR for the entire LAC region and stratified them by country using the subpop option in Stata to retain appropriate weighting within strata.

Forest plots were generated in RStudio using the ggplot2 and dplyr libraries to present the APR by country. Data frames included point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for each of the 27 countries. Each plot displayed prevalence estimates as points with horizontal bars for the 95% CIs, and a vertical dashed line indicating overall prevalence.

Ethical aspects

We analyzed publicly available and anonymized secondary data from population-based surveys that included parental or guardian consent. As such, the study was exempt from ethical review under Directorial Resolution No. 012-DGIDI-CIENTÍFICA-2021. Data are openly available on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website (https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gtss/gtssdata/index.html).

RESULTS

We analyzed data from 36662 adolescents across 27 Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries. Of the total sample, 53.4% were female and 46.6% were male. The age distribution was as follows: 36.5% were aged 13 years, 36.7% were 14 years, and 26.8% were 15 years. Overall, 18.5% of adolescents reported exposure to tobacco smoke in their homes. In addition, 13.0% expressed an intention to smoke in the future (Table 1).

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics of adolescents aged 13–15 years, a cross-sectional analysis of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Latin America and the Caribbean, 2013-2021 (N=36662)

| Characteristics | n | %* |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 19984 | 53.37 |

| Male | 16678 | 46.63 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 13 | 13300 | 36.47 |

| 14 | 13850 | 36.7 |

| 15 | 9512 | 26.83 |

| Exposure to tobacco smoke in the home | ||

| No | 30357 | 81.51 |

| Yes | 6305 | 18.49 |

| Intention to smoke | ||

| No | 32592 | 86.98 |

| Yes | 4070 | 13.02 |

The prevalence of smoking intention was highest among male adolescents (14.1%). It increased with age, reaching 15.7% among those aged 15 years, 12.5% those aged 14 years, and 11.5% those aged 13 years. Adolescents not exposed to household tobacco smoke reported a slightly higher prevalence of smoking intention (13.2%) than those who were exposed (12.2%) (Table 2).

Table 2

Frequency of intention to smoke according to sociodemographic characteristics of adolescents aged 13–15 years, a cross-sectional analysis of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Latin America and the Caribbean, 2013-2021 (N=36662)

| Characteristics | Intention to smoke | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (N=32592) | Yes (N=4070) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | 0.171 | ||

| Female | 17901 (87.95) | 2083 (12.05) | |

| Male | 14691 (85.88) | 1987 (14.12) | |

| Age (years) | 0.147 | ||

| 13 | 11921 (88.47) | 1379 (11.53) | |

| 14 | 12319 (87.46) | 1531 (12.54) | |

| 15 | 8352 (84.31) | 1160 (15.69) | |

| Exposure to tobacco smoke in the home | 0.519 | ||

| No | 27087 (86.80) | 3270 (13.20) | |

| Yes | 5505 (87.77) | 800 (12.23) | |

The overall prevalence of household exposure to tobacco smoke was 18.5%. Some countries reported relatively low rates, including Peru (7.1%) and Honduras (9.0%), while others showed higher levels, particularly Uruguay (28.9%), Suriname (28.2%), and Chile (27.9%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Prevalence of exposure to secondhand smoke at home among adolescents aged 13–15 years, by country, a cross-sectional analysis of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Latin America and the Caribbean, 2013-2021 (N=36662)

The prevalence of smoking intention among adolescents in the 27 countries varies widely, with a global average of 13.02%. Costa Rica reported the lowest prevalence (4.5%; 95% CI: 3.2–6.3), while El Salvador exhibited the highest rate (40.3%; 95% CI: 36.1–44.8) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Prevalence of smoking intention among adolescents aged 13–15 years, by country, a cross-sectional analysis of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Latin America and the Caribbean, 2013-2021 (N=36662)

In the analysis of the association between household exposure to tobacco smoke and smoking intention among adolescents from 26 LAC countries, no statistically significant association was identified (APR=0.91; 95% CI: 0.69–1.19; p=0.487). However, a significant association was observed in Chile (APR=1.78; 95% CI: 1.33–2.37; p<0.001), Barbados (APR=1.98; 95% CI: 1.16–3.40; p=0.014), the Dominican Republic (APR=1.96; 95% CI: 1.21–3.17; p=0.010), Saint Lucia (APR=1.82; 95% CI: 1.05–3.18; p=0.035), Panama (APR=1.58; 95% CI: 1.12–2.23; p=0.012), and Uruguay (APR=1.77; 95% CI: 1.27–2.46; p=0.002). In these countries, exposure to tobacco smoke at home was significantly associated with a higher intention to smoke among adolescents (Table 3).

Table 3

Crude and adjusted associations between exposure to secondhand smoke at home and smoking intention among adolescents aged 13–15 years, by country, a cross-sectional analysis of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Latin America and the Caribbean, 2013-2021 (N=36662)

| Exposure to secondhand smoke at home | Smoking intention n (%) | Crude analysis | Adjusted analysis* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | PR | 95% CI | p | APR | 95% CI | p | |

| LAC | ||||||||

| No ® | 27087 (86.8) | 3270 (13.2) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 5505 (87.8) | 800 (12.2) | 0.93 | 0.74–1.17 | 0.519 | 0.91 | 0.69–1.19 | 0.487 |

| Antigua | ||||||||

| No ® | 986 (94.8) | 55 (5.2) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 174 (92.9) | 13 (7.1) | 1.36 | 0.73–2.53 | 0.332 | 1.39 | 0.74–2.60 | 0.299 |

| Argentina | ||||||||

| No ® | 405 (86.6) | 56 (13.5) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 124 (88.6) | 18 (11.4) | 0.85 | 0.40–1.81 | 0.646 | 0.81 | 0.41–1.60 | 0.517 |

| Bahamas | ||||||||

| No ® | 542 (92.8) | 40 (7.2) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 122 (93.3) | 10 (6.6) | 0.93 | 0.41–2.11 | 0.851 | 0.93 | 0.42–2.05 | 0.845 |

| Barbados | ||||||||

| No ® | 696 (92.4) | 60 (7.6) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 98 (84.7) | 20 (15.3) | 2.03 | 1.18–3.48 | 0.012 | 1.98 | 1.16–3.40 | 0.014 |

| Belize | ||||||||

| No ® | 737 (95.2) | 38 (4.8) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 116 (95.9) | 5 (4.1) | 0.85 | 0.32–2.26 | 0.732 | 0.87 | 0.34–2.27 | 0.776 |

| Bolivia | ||||||||

| No ® | 1266 (86.4) | 194 (13.6) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 142 (79.9) | 33 (20.1) | 1.47 | 0.98–2.20 | 0.061 | 1.45 | 0.97–2.16 | 0.069 |

| Chile | ||||||||

| No ® | 2360 (92.3) | 209 (7.7) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 756 (86.6) | 110 (13.4) | 1.75 | 1.27–2.39 | 0.001 | 1.78 | 1.33–2.37 | <0.001 |

| Costa Rica | ||||||||

| No ® | 1072 (95.5) | 52 (4.5) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 149 (95.3) | 8 (4.7) | 1.06 | 0.43–2.62 | 0.901 | 1.07 | 0.43–2.65 | 0.884 |

| Cuba | ||||||||

| No ® | 1179 (92.3) | 97 (7.7) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 430 (92.4) | 35 (7.6) | 0.98 | 0.54–1.79 | 0.957 | 0.97 | 0.53–1.77 | 0.907 |

| Ecuador | ||||||||

| No ® | 1557 (88.3) | 193 (11.7) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 207 (81.7) | 43 (18.3) | 1.57 | 0.78–3.17 | 0.199 | 1.57 | 0.78–3.17 | 0.196 |

| El Salvador | ||||||||

| No ® | 1,069 (60.3) | 659 (39.7) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 104 (54.1) | 91 (45.9) | 1.16 | 0.85–1.58 | 0.334 | 1.15 | 0.85–1.56 | 0.349 |

| Grenada | ||||||||

| No ® | 961 (94.3) | 58 (5.7) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 157 (90.6) | 14 (9.4) | 1.66 | 0.99–2.77 | 0.054 | 1.58 | 0.92–2.72 | 0.095 |

| Guatemala | ||||||||

| No ® | 1105 (89.3) | 125 (10.7) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 181 (90.8) | 18 (0.9) | 0.86 | 0.45–1.62 | 0.624 | 0.86 | 0.46–1.63 | 0.639 |

| Guyana | ||||||||

| No ® | 512 (90.6) | 47 (9.4) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 72 (92.2) | 7 (7.8) | 0.83 | 0.48–1.44 | 0.472 | 0.86 | 0.46–1.60 | 0.617 |

| Honduras | ||||||||

| No ® | 1022 (89.5) | 129 (10.5) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 107 (88.5) | 15 (11.5) | 1.10 | 0.54–2.23 | 0.780 | 1.10 | 0.54–2.23 | 0.795 |

| Nicaragua | ||||||||

| No ® | 1723 (86.6) | 276 (13.4) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 294 (85.2) | 51 (14.8) | 1.10 | 0.80–1.52 | 0.539 | 1.08 | 0.78–1.48 | 0.632 |

| Panama | ||||||||

| No ® | 1,266 (91.9) | 112 (8.1) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 196 (87.3) | 29 (8.7) | 1.58 | 1.12–2.23 | 0.010 | 1.58 | 1.12–2.23 | 0.012 |

| Paraguay | ||||||||

| No ® | 1422 (89.9) | 167 (10.1) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 385 (86.2) | 54 (13.8) | 1.36 | 0.95–1.95 | 0.095 | 1.32 | 0.92–1.88 | 0.123 |

| Peru | ||||||||

| No ® | 1363 (91.4) | 131 (8.6) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 112 (91.4) | 11 (8.6) | 1.00 | 0.46–2.15 | 0.993 | 1.00 | 0.46–2.16 | 0.998 |

| Dominican Republic | ||||||||

| No ® | 397 (87.1) | 55 (12.9) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 55 (75.6) | 15 (24.4) | 1.88 | 1.16–3.07 | 0.015 | 1.96 | 1.21–3.17 | 0.010 |

| Saint Lucia | ||||||||

| No ® | 660 (92.4) | 52 (7.7) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 135 (86.4) | 22 (13.6) | 1.77 | 1.01–3.12 | 0.046 | 1.82 | 1.05–3.18 | 0.035 |

| Suriname | ||||||||

| No ® | 566 (94.9) | 30 (5.1) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 226 (94.1) | 15 (5.9) | 1.16 | 0.64–2.11 | 0.597 | 1.20 | 0.69–2.09 | 0.495 |

| Trinidad | ||||||||

| No ® | 1171 (91.9) | 101 (8.1) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 215 (91.9) | 23 (8.1) | 0.99 | 0.49–2.01 | 0.988 | 1.03 | 0.52–2.03 | 0.936 |

| Uruguay | ||||||||

| No ® | 770 (92.7) | 76 (7.3) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 334 (86.3) | 54 (13.7) | 1.87 | 1.25–2.78 | 0.003 | 1.77 | 1.27–2.46 | 0.002 |

| Venezuela | ||||||||

| No ® | 1,739 (84.5) | 217 (15.5) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 513 (89.1) | 78 (10.9) | 0.71 | 0.45–1.11 | 0.129 | 0.69 | 0.42–1.12 | 0.126 |

| St. Vincent | ||||||||

| No ® | 521 (93.1) | 41 (6.9) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 101 (92.7) | 8 (7.3) | 1,04 | 0.49–2.23 | 0.910 | 1.04 | 0.48–2.26 | 0.924 |

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the association between household tobacco smoke exposure and smoking intention among never smokers in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Although no significant association was found at the regional level, country-specific analyses showed a relationship in Chile, Barbados, the Dominican Republic, Saint Lucia, Panama, and Uruguay, suggesting that the influence of the home environment varies according to sociocultural factors, regulations, and smoking patterns.

All countries analyzed have ratified the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which establishes the MPOWER package (monitoring, protection, cessation support, warnings, advertising bans, and tax increases)16,17. However, uneven implementation could explain part of the observed heterogeneity. Progress has been stronger in the non-Spanish-speaking Caribbean, South America, and North America, but weaker in Central America and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean17.

Uruguay illustrates these gaps: 10% of adolescents aged 13–15 years smoke, 41.5% report exposure in enclosed public places18, and 52.6% of those who bought cigarettes access loose cigarettes, an illegal practice in the country19. Nearly half see tobacco advertisements at points of sale, and most are exposed through media18. These figures highlight deficiencies in protection, advertising bans, and access control. Countries such as the United Kingdom and France have strengthened protection through laws banning smoking in vehicles with minors, demonstrating that targeted regulations in private settings can complement public smoke-free laws20,21.

In Barbados, weak enforcement of tobacco control policies, including weak advertising bans with unknown levels of compliance, has likely contributed to the continued normalization of smoking and the persistence of relatively high youth smoking rates, despite the country’s ratification of the FCTC22. In contrast, Mexico has integrated tobacco control into public health and child protection strategies through national campaigns and legal restrictions that promote smoke-free environments, including homes, thereby reinforcing norms that protect minors from tobacco exposure23.

Peru and Honduras reported the lowest household exposure, reflecting progress linked to national tobacco control policies24-28. In Peru, this decline coincides with the progressive enforcement of Law No. 28705 and its amendments, including stricter smoke-free regulations, advertising bans, and health warnings, as well as awareness campaigns on secondhand smoke harms24-26. In Honduras, reforms introduced through Decree No. 12-2011 and the Special Law for Tobacco Control strengthened restrictions on smoking in enclosed public spaces, advertising prohibitions, and sales limitations to minors27,28. The country also achieved a high MPOWER score in 2023, indicating broad population protection through smoke-free regulations29. In contrast, Chile, Suriname, and Uruguay had the highest exposure, despite ratifying the FCTC, pointing to enforcement gaps18,30. While over 100 countries have implemented at least one MPOWER measure at the highest level, only Brazil and Turkey have achieved full compliance31. Marketing tactics, including appealing packaging and point-of-sale visibility, continue to affect adolescents despite legal restrictions32,33. Taxation also varies across the region, with high-tax countries not necessarily showing lower exposure due to illicit sales and single-cigarette availability34.

The intention to smoke among adolescents in El Salvador (40.3%) is substantially higher than in Costa Rica (4.5%), reflecting a considerable disparity in the predisposition to tobacco use. In El Salvador, most adolescent smokers consume an average of less than one cigarette per day, and over 70% start before the age of 14 years, indicating early initiation as a key driver35. In contrast, in Costa Rica, shows lower smoking intention, likely linked to stronger family and school-based prevention efforts: most adolescents discuss smoking risks at home, and over half receive information on tobacco harms at school, which may contribute to delaying or preventing initiation36.

The observed association between household exposure to tobacco smoke and smoking intention in certain LAC countries reinforces the notion that the family environment plays a decisive role in shaping adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors toward tobacco use. Exposure at home may influence smoking intention through social and psychological mechanisms such as modeling, normalization, and reduced risk perception. Adolescents who frequently witness smoking within the household are more likely to perceive it as acceptable and develop curiosity or positive expectancies toward tobacco use8,10,11,13. In addition, permissive family dynamics, marked by limited communication, inconsistent supervision, and low perceived harm, may increase susceptibility to experimentation10,11. These findings highlight the importance of the home as a key setting for prevention and underscore the need for further research to confirm these mechanisms and inform evidence-based public policies.

Limitations

One main limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which prevents establishing causality. Self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias and potential misclassification, which could affect accuracy and reliability, especially in adolescents influenced by their social environment. Another limitation is the exclusion of countries due to missing outcome data. Brazil, Colombia, Dominica, Haiti, Montserrat, Mexico, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and the Virgin Islands were excluded. Jamaica was also omitted from association analysis because its data structure (one stratum and one primary sampling unit), prevented the calculation of confidence intervals and reliable estimates. In addition, the limited characterization of adolescents’ sociodemographic characteristics in the GYTS poses challenge for interpretation. Key variables such as socioeconomic status, family environment, parental education, tobacco risk perception, and cigarette access are not standardized, limiting model adjustment and increasing the potential for residual confounding. Socioeconomic and regulatory differences between countries may also influence exposure and smoking intention, affecting effect estimates. Despite these limitations, the GYTS remains a reliable and timely data source. Its standardized WHO-endorsed methodology, ensures national representativeness and validity, allowing country comparisons and supporting the generalizability of the study findings to inform tobacco control strategies in LAC.

CONCLUSIONS

At the regional level, no statistically significant relationship was identified between exposure to tobacco smoke at home and the intention to smoke among adolescents from LAC. However, country-specific analysis showed this relationship in Chile, Barbados, the Dominican Republic, Saint Lucia, Panama, and Uruguay. This suggests that the influence of the family environment on tobacco initiation is not homogeneous across the region and may be shaped by sociocultural factors, local regulations, and household consumption patterns. Longitudinal studies are recommended to assess directionality and explore modulating contextual factors. Confounding variables not included in this analysis should be considered. These findings may help inform future research and support the design of context-sensitive strategies to reduce adolescent exposure to tobacco smoke, while acknowledging that evidence from cross-sectional studies is insufficient to establish causal relationships.