INTRODUCTION

Due to breakthroughs in HIV treatment that have prolonged the life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLHIV) and ensured viral undetectability when taken as prescribed1, HIV prevalence in Germany and Austria has declined in recent decades2. As HIV incidence has decreased and life expectancy of PLHIV has improved, the age distribution of PLHIV has shifted toward the elderly3,4. To ensure optimal quality of life throughout the lifespan and to promote individualized treatment, PLHIV holistic care is required, particularly in the context of polypharmacy.

However, many PLHIV continue to have unmet treatment needs, which can compromise their health and wellbeing, and have far-reaching consequences for the individual that cannot be traced to the virus alone5. Drug-drug interactions, medication resistance, tolerability issues, and inconvenient dosing schedules may be encountered by PLHIV with their HIV treatment6. The HIV-specific and medical concerns associated with daily oral antiretroviral therapy (ART) can make it difficult for many PLHIV to achieve and maintain adequate adherence7-10. During 2019–2020, there were 5565 new HIV diagnoses in Germany (G) and 388 in Austria (A)4. The persistent transmission of new infections suggests many people are living with HIV without being diagnosed, or being on treatment as prescribed.

Innovations in HIV treatment have led to the development of alternative options to daily oral dosing that are effective, well-tolerated, and require fewer doses, providing greater flexibility to enhance adherence11-13. These new treatment options provide people living with HIV with a wider selection of medication options, giving them more control over their treatment14,15. People living with HIV deserve options for tailoring their treatment according to both medical, as well as personal or lifestyle needs. Patients’ right to choose, however, is only meaningful if they are well-informed and actively involved in treatment decisions. HIV healthcare providers (HCPs) can assist by providing accurate information about new therapies to all patients, encouraging full adherence, and reevaluating treatment regimens to address patient concerns about HIV medication or other added treatments16. To address the physical and psychological needs of their patients, HCPs must first comprehend the characteristics of the PLHIV population that place them at a greater risk of non-adherence to treatment due to a range of unmet needs.

There is a paucity of studies examining the whole spectrum of unmet needs among PLHIV, including unmet requirements related to medication, involvement in care, and contextual issues such as stigma that affect adherence. For patients to assume responsibility for their treatment plan and adhere to their prescribed medication, all these factors must be considered simultaneously. Stigma, for instance, can render PLHIV more susceptible to anxiety, stress, and depression, as well as inhibit health seeking behaviors, leading to poor physical and mental health, social isolation, and impaired quality of life8,17-19. Consequently, while many healthcare providers (HCPs) may consider only HIV-specific issues or other individual-level determinants20, it is equally important to consider contextual or social factors that are pervasive and ingrained at the personal, health system, and broader community levels, and which pose significant barriers to care access. This analysis focused on local data from PLHIV in Germany and Austria to investigate self-reported unmet needs regarding HIV medications, patient involvement in prescription decision-making, and privacy/confidentiality concerns (stigma) in relation to HIV status.

METHODS

Data sources

The Positive Perspectives survey is an international, web-based survey of PLHIV designed to better understand their evolving needs16,21-23. The first wave (PP1) was conducted in 9 countries (n=1111) between November 2016 and April 2017 and targeted PLHIV aged ≥18 years, regardless of their treatment status. The focus of PP1 was on HIV stigma and treatment challenges in the immediate aftermath of being diagnosed with HIV. Positive Perspectives 2 (PP2) was conducted in 25 countries (n=2389) in 2019–2020 and surveyed only PLHIV on ART. PP2 focused on emotional, psychological, and physical problems associated with ART intake, as well as communication quality with HIV care providers. PP1 (Germany n=140; Austria n=50) and PP2 (Germany n=120; Austria n=50) both comprised Germany and Austria. Data were evaluated from both waves to capture the complete spectrum of treatment challenges along the HIV treatment cascade. Single IRB review for the multi-site study was done by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (no. 18–080622).

Measures

Clinical measures

Both PP1 and PP2 surveys collected self-reported data on key clinical metrics such as self-rated health, viral load, adherence, indicators of quality of life, ART satisfaction, participants’ perceptions of whether their HIV medications and overall HIV management could be improved, and their perceived self-efficacy in managing their HIV medications as prescribed.

Unmet needs associated with ART

Participants were asked about their ART dosing frequency, worries about taking their HIV medications as prescribed, and their treatment preferences. Consistent with previous reports, polypharmacy was defined in PP2 as taking ≥5 medications per day, or being treated for ≥5 conditions21. PP2 also identified the reasons for missing ART in the previous month, willingness to try new HIV medications, and which treatment goals were deemed most important among people who had lived with HIV for at least a year.

Unmet needs associated with patient-provider engagement

Several facets of patient-provider engagement and communication were assessed in both PP1 and PP2, including how well HCPs acknowledged patients’ wishes to be involved in their care, informed patients of new medical advancements and treatment options, and addressed patients’ concerns/priorities. PLHIV were also asked how comfortable they felt speaking with their HCPs about various treatment challenges and concerns, as well as perceived communication hurdles with their HCPs. Information was further collected on preferred communication channels, perceived stigma in healthcare environments, and collaborative decision making in HIV care.

Unmet needs associated with privacy and confidentiality of HIV status

In PP1, participants were considered stigmatized if they reported experiencing physical, verbal, institutionalized, social, or self-stigma: ‘occasionally’, ‘often’, or ‘very often’ (vs ‘never’). The several reasons why PLHIV occasionally refuse to share their HIV status were also assessed in the survey.

Analyses

The data were summarized using percentages and means using R Version 3.6.2. We produced overall and stratified prevalence estimates for outcomes of interest, and compared groups using two-tailed chi-squared tests. Results were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. The two surveys’ unique, but related themes, were integrated to better understand PLHIV experiences, challenges, and aspirations from diagnosis to ART initiation and beyond. We chose the survey wave with the most extensive information on each unmet need to construct a comprehensive narrative. We did not make assumptions regarding wave-to-wave comparisons, nor did we append data across waves within the analysis. Using PP2 data from both countries combined, adjusted prevalence ratios (APRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed in a multivariable Poisson regression model to assess the relationship between having one’s treatment priorities satisfied and several markers of quality of life, adherence, and self-rated health, adjusting for age, gender, comorbidities, and country.

RESULTS

Population characteristics and self-rated health

The majority of PP1 participants were male (75% in Germany, 76% in Austria), employed full- or part-time (Germany 55%, Austria 48%), identified as ‘homosexual/gay/lesbian’ (G 71%, A 64%), and virally suppressed (G 91%, A 94%). Of surveyed PLHIV, Germany had 10% foreign-born people, while Austria had 28%. Austria (52%) had more post-secondary school graduates than Germany (44%) (Table 1). Over half of individuals reported optimal overall health (G 68%, A 78%), physical health (G 68%, A 72%), mental health (G 58%, A 60%), and sexual health (G 57%, A 62%). Overall, 54% in Germany vs 72% in Austria reported they enjoyed living; 63% in Germany vs 76% in Austria felt in control of their lives; 57% in Germany vs 72% in Austria were pleased with their health; and 57% and 66% in Germany and Austria, respectively, were pleased with their social activity. Furthermore, 58% of German and 42% of Austrian participants were in a relationship, whether living together or apart. Of the 37% [52/140] German and 28% [14/50] Austrian participants in a co-habiting relationship, most reported having an HIV-negative partner (G 60% [31/52], A 79% [11/14]) and their partner was aware of their HIV status (G 96% [50/52], A 100% [14/14]). PLHIV in a relationship in which their HIV status was known reported receiving multifaceted support from their partner including having someone to talk about their HIV to receive emotional support (G 80% [40/50], A 71% [10/14]), reminding them to take their HIV medication (G 56% [28/50], A 64% [9/14]) or accompanying them to their HCP appointments (G 34% [17/50], A 28% [4/14]) (Table 1).

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics and self-rated health indicators among people living with HIV, in a cross-sectional survey, Positive Perspectives Wave 1 (2016–2017), Germany (N=140) and Austria (N=50)

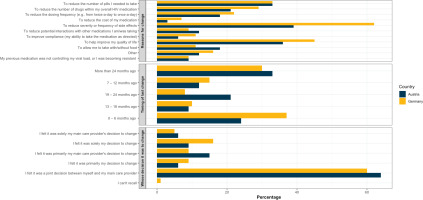

Experiences in the immediate aftermath of HIV diagnosis

Overall, 31% of German participants and 32% of Austrian PP1 participants were diagnosed with HIV within the previous five years. One-third of all PP1 participants (G 29%, A 36%) did not recall receiving counseling or emotional support after their HIV diagnosis from their main HCP (Table 2). Furthermore, within analysis of PP1 data, variations were seen in the two countries in relation to their recall of where they sought emotional support when they were newly diagnosed. Austrians relied on their primary HIV care provider the most (54%), whereas Germans relied on close friends the most (42%). Furthermore, only 21% of German participants would turn to their HCP for emotional support if they needed such help now. However, German participants visited their main HIV care provider 5.33 times (Austria, 4.2 times) on average per year, which was more frequent than reported visits to their non-HIV doctor (G 1.95 vs A 2.52 average visits per year). Of German PLHIV ever on ART, 78% [107/138] had ever switched regimens compared to 66% [33/50] in Austria. Half (52%; 56/107) of the ART switches ever made were done in the past year in Germany, including both first-time and repeat switches, versus 36% (12/33) in Austria that were done in the past year. The top reasons for switching ART among those who ever switched, were to reduce side effects (G 62% [66/107] vs A 39% [13/33]), improve quality of life (G 45% [48/107] vs A 36% [12/33]), reduce the number of pills they had to take (G 33% [35/107] vs A 33% [11/33]), reduce the number of drugs in their HIV medication (G 29% [31/107] vs A 21% [7/33]), and reduce dosing frequency (G 22% [24/107] vs A 18% [6/33]).

Table 2

Sources of emotional support and interactions with healthcare providers among people living with HIV, in a cross-sectional survey, Positive Perspectives Wave 1 (2016–2017), Germany (N=140) and Austria (N=50)

Current unmet treatment needs

While most participants currently on treatment were satisfied with their HIV medication in both surveys (PP1: G 87% [119/137], A 90% [44/49]), there were perceived unmet needs with the medication itself (emotional and psychosocial challenges associated with daily dosing), the process of treatment decision making (unmet desire for greater involvement in care), and contextual factors (e.g. stigma), which, while not caused by ART, could make its intake more difficult, as described in the subsections below.

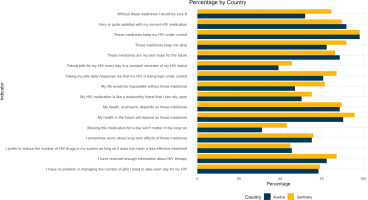

Unmet treatment needs associated with HIV medication

Of current ART users in PP1, 65% [32/49] of Austrian PLHIV were taking multi-tablet regimens compared to Germany (48%; 66/137). Of the 137 German and 49 Austrian participants currently on ART in PP1, most acknowledged the role ART played in controlling their viral load (98% in Germany and Austria each) and keeping them alive (G 90%, A 78%), although they had concerns about their medication. These concerns included stress or pressure to take their HIV medication on time every day (G 34%, A 37%), side effects (G 34%, A 22%), the perception that ‘being tied’ to their HIV medication limits their daily life (G 22%, A 37%), the number of drugs in their regimen (G 21%, A 27%), and the medicine’s taste (G 7%, A 12%) (Figure 1, and Supplementary file Table 1). Analysis of participants’ ART-related emotional and psychological concerns within the past month revealed that 26% of German participants found their treatment burdensome (14% in Austria) and 16% stated their medicine made it difficult to live a normal life (8% in Austria).

Figure 1

Attitudes towards HIV medication among people living with HIV who were currently on treatment, in a cross-sectional survey, Positive Perspectives Wave 1 (2016–2017), Germany (N=137) and Austria (N=49)

In the second wave of Positive Perspectives (PP2), which was comprised entirely of those currently on ART, participants revealed ART unmet needs of a psychosocial nature as well. These included feelings that taking ART daily constantly reminded them of their HIV status (G 52%, A 66%), increased the likelihood of unwanted disclosure of their HIV status (G 42%, A 34%), and brought back bad memories (G 37%, A 28%). While the leading reason for missing ART at least once in the past 30 days for both countries was report as falling asleep during dose time or being busy (G 33%, A 34%), a diversity of physical, mental, and psychosocial ART barriers were linked to missing treatment (Figure 2). Comparing persons from Germany and Austria in PP2, the reason for missing ART at least once in the previous 30 days that differed the most between the two countries was privacy concerns (G 26% vs A 14%) (Figure 2). Other reasons for missing ART at least once in the previous 30 days included the following: being depressed/overwhelmed (G 23% vs A 18%), inconvenient dosing schedules or problems taking ART with food (G 22% vs A 12%), side effects (G 21% vs A 12%), ran out of pills (G 18% vs A 24%), and bored taking HIV medication every day (G 20% vs A 14%) (Figure 2).

Unmet treatment needs associated with treatment decisions

Many PLHIV showed low HIV treatment literacy, information asymmetry with their HCP, limited engagement in treatment decisions, and low self-efficacy in discussing treatment issues with HCPs. Some PP1 participants currently on treatment called their HIV medications a ‘mystery’ (G 8% [11/137], A 14% [7/49]), while many of PP2 participants who were all on treatment were unaware of the number of medicines in their ART regimen (G 31%, A 50%). Within the context of multiple response options assessed in PP1 data among all participants, variations were seen in the percentage of participants reporting that their HCP explained to them the reason for offering a specific medicine (G 86%, A 76%), actively involving them in treatment decisions (G 78%, A 72%), providing a range of viable treatment options and letting them choose one (G 72%, A 70%), or supporting their (i.e. the patient’s) own medicine decisions (G 56%, A 60%) (Table 2). In Germany (60%; 64/107) and Austria (64%; 21/33) each, under two-thirds of PP1 participants who ever switched ART recalled a joint decision-making with their HCP (Figure 3, and Supplementary file Table 1). In PP2, 72% of Germans and 76% of Austrians said their HCP asked their viewpoint before prescribing treatment. Half of the PP2 participants (G 51%, A 54%) wanted greater involvement in making treatment decisions. Germany had significantly fewer PP2 participants than Austria who understood their HIV treatment (G 62% vs A 84%; p=0.004) or who said their HCP gave them enough information to make decisions (G 65% vs A 82%; p=0.028). Nonetheless, German participants were more comfortable discussing specific treatment issues with their doctors, such as worries about drug-drug interactions (G 68% vs A 52%; p=0.044), long-term consequences of ART (G 67% vs A 50%; p=0.042), and missing ART (G 61% vs A 44%; p=0.044). Meanwhile, when discussing new HIV therapies, 68% in Germany and 72% in Austria indicated that their HCP regularly discussed new treatment options with them. Within the PP2 sample, the percentage of those who ever wanted a different ART to that they were on, but admitted to never discussing their preference with their HCP, was nearly two-fold greater in Germany (29%; 16/56) than in Austria (14%; 2/14). Overall, the HCP communication barrier whose frequency of occurrence differed significantly between the two nations was a lack of time or opportunity during appointments (G 8% vs A 24%; p=0.003).

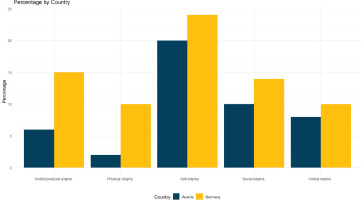

Unmet treatment needs regarding privacy and confidentiality

Within PP1 where stigma was assessed, the results showed that institutionalized stigma was among the two most prevalent types of stigmas experienced by Germans (15%), alongside self-stigma. Self-stigma was the most prevalent form of stigma in both Germany (24%) and Austria (20%). Additionally, social stigma was reported by 14% of participants in Germany and 10% in Austria. In contrast, institutionalized stigma accounted for only 6% of reported stigma among Austrian participants, making it one of the two least widespread types of stigmas. The other less prevalent type in Austria was physical stigma, which had a prevalence of 2% (Figure 4, and Supplementary file Table 2). At least twice as many PP1 participants in Germany as in Austria reported being mistreated or denied services (G 16% vs A 8%); or having healthcare providers being afraid or unwilling to treat them (G 17% vs A 6%). When asked what could be done to remove HIV stigma in general, the most popular response from PP1 participants in Germany, aside from more public education, was targeted training of healthcare practitioners (48%), 16 percentage points more than the same response in Austria (32%) (Supplementary file Table 2). Regarding openness sharing their HIV status, less than 1 in 5 PP1 participants affirmed: ‘I am generally open to talking about my status (G 17%, A 18%) (Supplementary file: Figure 1 and Table 2). The percentage who had shared their HIV status with different people around them is shown in Supplementary file Figure 2. Indicators of anticipated stigma were higher among Austrian individuals: 82% reported hiding their HIV medications at least occasionally (40 of 49 on treatment), compared to 69% of German PP1 participants (94 of 137 on treatment). In PP2, the prevalence of hiding HIV medications in the previous six months was 17 percentage points higher in Austria than in Germany. Similarly, 36% of Austrian participants in PP2 indicated they would be anxious if someone discovered they were taking HIV medication, compared to 27% of Germans. Furthermore, twice as many PLHIV in Austria as in Germany reported in PP2 that they had ever refused to disclose their HIV status for the following reasons: fear of being treated differently (G 37% vs A 64%; p=0.001); fear of the disclosure affecting their friendships (G 27% vs A 46%; p=0.001); fear of gossip (G 25% vs A 54%; p=0.001); and fear of romantic discrimination (G 18% vs A 46%; p<0.001).

Goals for treatment

Most PP2 participants were optimistic about future breakthroughs in the HIV care continuum improving their overall health and wellbeing (G 76%, A 82%). Furthermore, many reported willingness to use novel regimens, such as longer acting HIV regimens (G 46%, A 52%). Within the pooled PP2 sample from both countries (n=170), preference for longer acting HIV regimens was significantly higher among those reporting versus not reporting the following challenges: perception that daily ART dosing is stressful (G 73% vs A 40%; p=0.001), perception that daily ART intake limits quality of life (G 63% vs A 41%; p=0.009), perception that daily dosing cues bad memories (G 62% vs A 40%; p=0.007), worried about missing their ART (G 63% vs A 38%; p=0.002), afraid of taking more and more medicines with age (G 58% vs A 39%; p=0.016), worried about the impact of ART on their body (G 63% vs A 36%; p=0.001), worried about the risk of drug-drug interactions (G 60% vs A 40%; p=0.011), fear of long-term negative effects of ART (G 60% vs A 38%; p=0.004), and fear of running out of treatment options (G 61% vs A 42%; p=0.024).

The following current treatment priorities differed significantly by country among PP2 participants who had lived with HIV for one year or longer (Germany, n=114; Austria, n=49): ensuring viral suppression (G 45% vs Austria 65%; p=0.016); reducing the number of medicines in their ART regimen (G 30% vs A 55%; p=0.002), lowering the risk of long-term negative consequences from ART intake (G 44% vs A 63%; p=0.023); increasing dosing flexibility (G 27% vs A 43%; p=0.049); and improving ability to manage HIV-related illnesses (G 27% vs A 63%; p<0.001). Overall, 2 in 3 PLHIV in the PP2 sample (G 65%, A 66%) believed their healthcare provider satisfies their specific medical needs and prioritizes their health concerns.

In a pooled multivariable analysis of the two countries’ PP2 data that controlled for the presence of comorbidities, age, gender, and country, PLHIV who reported that their HCP prioritizes their health concerns had a lower likelihood of reporting polypharmacy (adjusted prevalence ratio, APR=0.56; 95% CI: 0.53–0.60) or believing there was room for improvement with their HIV medication or overall HIV care (Figure 5). Conversely, the belief that their HCP prioritizes their health concerns was positively associated with optimal health in all domains, including overall health (APR=2.58; 95% CI: 2.45–2.72). It was also positively linked to higher self-efficacy in managing ART doses (APR=1.98; 95% CI: 1.89–2.07), and being satisfied with one’s current HIV medicine (APR=2.40; 95% CI: 2.29–2.52).

DISCUSSION

Overall, participants reported generally high levels of selfrated health and viral suppression, as the main treatment goals. However, consistent with previous studies, we found that PLHIV also had several psychosocial and emotional treatment challenges, which can negatively impact treatment adherence and overall health24-29. For instance, a quarter of German participants skipped at least one ART dose in the previous 30 days due to concerns about privacy. These findings suggest many PLHIV may benefit from an alternative to daily oral ART due to HIV-specific and oral dosing-related difficulties. Despite being satisfied with their treatment, most participants were open to longer acting regimens. In prior studies, many PLHIV believed that a long-acting ART would assist them in overcoming difficulties associated with daily oral ART, such as pill burden14,15. Less than 1 in 5 PP1 participants in Germany and Austria were comfortable sharing their HIV status with others, underscoring the ongoing need for HIV education, support, and reduction of stigma to improve the overall well-being and quality of life for PLHIV. Addressing these unmet needs as part of a holistic approach to the HIV care continuum may improve the health-related quality of life of PLHIV by increasing the flexibility and choice of ART delivery. As patient care progresses from curing diseases to promoting wellness and quality of life, patient–provider communication must also migrate from prescriptive to individualized, to accommodate underlying comorbidities, preferences, values, lifestyle, and concerns that may vary from individual to individual. Adapting the HIV care continuum to the patient’s needs can improve health outcomes in addition to boosting convenience and quality of life30,31. This is supported by our result that PLHIV whose health needs and priorities were met by their HCP were more likely to report optimal self-rated health and self-efficacy in managing their ART doses. To improve health outcomes among PLHIV, it is necessary to address unmet needs throughout the entirety of the HIV treatment cascade, from diagnosis, to treatment initiation, to ensuring optimal quality of life. Our findings underscore the need for healthcare providers and patients to consider speaking more openly about challenges PLHIV experience in relation to treatment as well as living with HIV in general.

Despite their eagerness to participate in their own care, several PLHIV in our study reported being excluded from HIV treatment decisions. Language hurdles and biases may hinder communication between HCPs and vulnerable groups, such as refugees and migrants32. However, patients are motivated to continue therapy through positive interactions with caregivers and active participation in care16. Mental health and substance use disorders, inadequate health coverage, insecure housing and homelessness, stigma, prejudice, fear, geographical hurdles to access care, and a lack of social and structural support have been recognized as impediments to optimal care involvement among PLHIV9. By removing communication barriers, PLHIV can be helped to fulfil the fourth of the ninety goals (better quality of life).

UNAIDS launched the accelerated ‘95-95-95’ strategy to eradicate AIDS by 203033. To achieve these objectives, it will be necessary to identify and address the numerous unmet needs that may hamper ART adherence. By the end of 2020, Germany met the second indicator (increasing the proportion of diagnosed individuals on ART) and significantly surpassed the third indicator (increasing the proportion of virally suppressed individuals on treatment) of the UNAIDS 90-90-90 treatment objective34. Germany, however, did not meet the first 90 target of increasing the percentage of all PLHIV who are aware of their HIV status. Indeed, as of 2018, an estimated 11300 people were uninformed of their HIV status (13% of the 86100 PLHIV in the country)35. For Austria, there were an estimated 542 individuals who were unaware of their HIV status in 2018 (8% of the 7079 PLHIV in the country), and 934 in total who were not on ART (13% of all PLHIV). Recent data indeed suggest that Austria met the first and second of the 90-90-90 indicators (i.e. increasing diagnosis and ART coverage)36.

HIV stigma, particularly at healthcare facilities, may inhibit HIV testing and linkage to the care continuum and promote internalized stigma, particularly among vulnerable groups such as migrants and rural inhabitants19,26-29. National and international frameworks advocate for the elimination of stigma9; nonetheless, intensified efforts are needed by all stakeholders (health professionals, support groups, media organizations, the community, and individuals) to guarantee that PLHIV have the right to healthcare that is culturally safe and stigma-free. As part of providing culturally safe care, members of the healthcare team should examine how their own beliefs, habits, and histories influence the care they provide to PLHIV and how they can better provide information and services in a non-threatening, non-judgmental, non-prejudiced manner that respects the personal, cultural, and religious views of each person living with HIV. Given that self-stigma was the most prevalent form of stigma among PLHIV in our study, stigma-reduction efforts are also required among PLHIV. Therefore, efforts to reduce stigma and prejudice should include both PLHIV and the community.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that the conclusions may not be generalizable beyond the setting or groups analyzed. Moreover, due to the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be inferred; only associations can be made. Non-response bias and the possibility of imprecise estimates among subgroups with relatively small sample sizes may also exist. Due to the web-based nature of data collection, estimates may be biased towards those more likely to have internet access, such as younger adults, individuals with higher socioeconomic status, and those who are more technologically inclined or have a stronger preference for digital platforms. The self-reported results may also be susceptible to misclassification and other social or cognitive biases.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite reporting ART satisfaction, PLHIV continue to have various unmet treatment needs that jeopardize optimal adherence and quality of life. Our research reveals that there are opportunities to improve HIV management at various points along the treatment cascade, such as by including patients in treatment planning, tackling stigma, and providing flexible treatment regimens tailored to the patient’s individual circumstances. Individualized care was associated with improved health outcomes and should be encouraged in all aspects of treatment, particularly when starting or switching medications. HCPs should inform patients about novel treatment options and solicit their opinions and preferences to improve their health-related quality of life. Flexible regimens that could accommodate the diverse needs of PLHIV exist and when personalized to the patient, may increase treatment satisfaction and support overall health outcomes. To better comprehend and adopt the patient’s treatment preferences, discussions between patients and clinicians should be optimized in a manner that is interactive, ongoing, and empathetic.