INTRODUCTION

Smoking is a major modifiable risk factor that significantly contributes to premature death due to cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and pulmonary diseases globally1. Despite widespread public awareness of the negative health consequences of smoking tobacco1,2, there is a substantial number of people both in developed and developing countries who continue to smoke3,4 due to nicotine addiction3 and/or lack of motivation to quit and/or intense marketing of the tobacco products. Indeed, attempts to quit smoking are often unsuccessful. Smoking cessation is a process conceptualized as occurring in a series of stages4, requiring that one first makes a quit attempt and then succeeds in that quit attempt by maintaining abstinence. Notably, most smokers unsuccessfully attempt quitting smoking many times before achieving long-term abstinence5, with more than half of quit attempts ending in relapse6,7.

Healthcare providers play a critical role in facilitating smoking cessation8,9. The World Health Organization (WHO) and clinical guidelines state that the physicians should actively advise smokers to quit10,11. Healthcare providers are better placed to advise smokers to quit since they are perceived as credible and authoritative on health issues, and their advise is appropriate and acceptable12. Stead et al.13, concluded that brief simple advise to a smoker increases the likelihood that he/she will quit smoking and remain abstinent even after 12 months. Furthermore, intensive advise would yield higher rates of cessation. Studies have also shown that many smokers visiting their healthcare providers would like to quit smoking for health reasons14,15, however, they are not advised to quit16. Despite evidence supporting the effectiveness of brief advise13,17, most healthcare providers rarely advise and assist their patients in quitting smoking due to lack of skills, low self-efficacy, lack of time and referral sources18,19, or because they do not perceive smoking cessation care to be their responsibility20,21.

Zambia, like other Sub-Saharan African countries, is undergoing a rapid epidemiological transition characterized by a shift from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases (NCDs)22,23. With four of the top ten leading causes of death in Zambia (ischemic heart diseases, hypertensive disease, tuberculosis, and stroke)24 caused, exacerbated, or associated with tobacco smoking1,2, healthcare providers in Zambia should prioritize smoking cessation advise to all smokers who present to their hospital or clinic. The aim of this study is twofold: 1) to estimate the proportion of smokers in Zambia who receive smoking cessation advise from their healthcare providers; and 2) to estimate the prevalence and factors associated with quit attempts in Zambia. To our knowledge, there is a paucity of research conducted on smoking cessation advise in Zambia. This research will contribute to formative smoking cessation guidelines and education programs in Zambia, thereby addressing a leading public health concern.

METHODS

Source of data

This study used secondary data from the Zambia WHO-STEPS Survey 2017 for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) prevalence and risk factors, mental and oral health. The Zambia STEPS survey is a cross-sectional national survey designed to obtain data representative of the adult population, aged 18–69 years, living in Zambia. The STEPS survey uses a multi-stage cluster sampling technique and utilizes the household listing from the Zambia Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment (ZAMPHIA). The first stage of sampling was a selection of Standard Enumeration Areas (SEAs) from each of the 10 provinces using probability proportional to size (PPS). In the second stage, 15 households in the rural SEAs and 20 households in urban SEAs were selected systematically using appropriate sampling intervals based on the number of households in that SEA. In the third stage, one member of the household who was eligible was selected for an interview. The questionnaire administered to survey participants included demographic data, as well as physical and biochemical measurements. Overall, 4301 participants were included in the survey, with a response rate of 77.7%. Details of the WHO-STEPS methodology can be found elsewhere25.

Eligibility criteria

All participants aged 18–69 years who reported ‘yes’ to the question ‘Do you currently smoke any tobacco products, such as cigarettes, shisha, cigars, or pipes?’ during the WHO-STEPS Survey were eligible for the study.

Variables and measurements

Primary outcomes

There were two primary outcome variables of interest: 1) receipt of advise to quit smoking among current smokers who visited a doctor or other healthcare worker in the past 12 months (yes/no response to the question ‘During any visit to a doctor or other health worker in the past 12 months, were you advised to quit smoking tobacco?); and 2) past year quit attempt status (yes/no response to the question ‘During the past 12 months, have you tried to stop smoking?’).

Sociodemographic variables

Age, gender (male/female), residence (rural/urban), education level (no or less than primary, primary, secondary school, or higher education), marital status (never married or married/cohabiting), and employment status (self-employed/formally employed, unemployed/retired, or nonpaid/student/homemaker).

Behavioral and psychological variables

Current smokers who responded ‘yes’ to the question ‘Have you consumed any alcohol within the past 30 days?’ were classified as alcohol consumers, whereas those who reported ‘no’ were classified as non-consumers. Current smokers were asked: ‘During the past 12 months, have you attempted suicide?’. Those who answered ‘yes’ were classified as recent suicide attempt whereas those who answered ‘no’ were classified as no recent suicide attempt.

Clinical variables

Two specific questions were asked to assess history of cardiovascular disease (CVD): 1) ‘Have you ever had a heart attack?’ (yes/no); and 2) ‘Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health worker that you have raised blood pressure or hypertension?’ (yes/no). History of metabolic disease (diabetes mellitus) was assessed by asking: ‘Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health worker that you have raised blood sugar or diabetes?’ (yes/no).

Statistical analysis

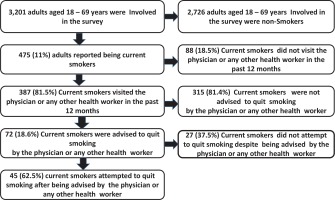

The first analysis included 475 current smokers and the second analysis included 387 current smokers who visited a doctor or other healthcare workers in the past 12 months (Figure 1). We calculated the proportion of smokers who received advise to quit smoking and attempted to quit smoking, overall and stratified by sociodemographic, behavioral and psychological, and clinical variables. Categorical variables are reported as percentages. Chi-squared tests of association were used to determine associations between quit attempts and selected predictor variables. Logistic regression models producing unadjusted (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were used to assess the association between advise to quit and quit attempt. Covariates were determined a priori and included in the full model regardless of the statistical significance in the univariate regression model (age, gender, recent suicide attempt, heart attack, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus). Statistical significance in the adjusted model was set at a two-sided 0.05 level. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 15.

Ethical approval

The University of Zambia Research Ethics Committee (UNZABREC) approved the STEPS Survey and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants26.

RESULTS

Characteristics of overall current smokers included in the analysis

Among the 475 smokers included in the analysis, more than half were aged 18–44 years (63.8%) (Table 1). The majority of the smokers were men (87.2%), of rural residence (70.9%), with no education or less than primary (42.6%), married/cohabiting (68.8%), and self-employed/formally employed (60.9%). In terms of comorbidities, 2.9% had a history of heart attack, 16.9% had hypertension, and 4.2% had diabetes mellitus. Recent suicide attempt and alcohol consumption was reported in 11.9% and 75.6% of smokers, respectively. Less than half (47.6%) of the current smokers included in the analysis attempted to quit smoking.

Table 1

Characteristics of adult smokers according to whether they were advised to quit and made an attempt to quit, WHO-STEPS Survey 2017, Zambia

| Characteristics | Overalla N (%) | Advised to quit n (%) | Not advised to quit n (%) | Overallb N (%) | Attempt to quit n (%) | No attempt to quit n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 387 (100) | 72 (18.6) | 315 (81.4) | 475 (100) | 226 (47.6) | 249 (52.4) |

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18–29 | 108 (27.9) | 17 (23.6) | 91 (28.9) | 130 (27.4) | 67 (29.7) | 63 (25.3) |

| 30–44 | 137 (35.4) | 23 (31.9) | 114 (36.2) | 175 (36.4) | 76 (33.6) | 99 (39.8) |

| 45–59 | 99 (25.6) | 24 (33.4) | 75 (23.8) | 120 (25.3) | 65 (28.8) | 55 (22.1) |

| 60–69 | 24 (6.2) | 8 (11.1) | 35 (11.1) | 50 (10.5) | 18 (7.9) | 32 (12.9) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 337 (87.1) | 67 (93.1) | 270 (85.7) | 414 (87.2) | 207 (91.6) | 207 (83.1) |

| Female | 50 (12.9) | 5 (6.9) | 45 (14.3) | 61 (12.8) | 19 (8.4) | 42 (16.9) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 272 (70.3) | 48 (66.7) | 224 (71.1) | 337 (70.9) | 158 (69.9) | 179 (71.9) |

| Urban | 115 (29.7) | 24 (33.3) | 91 (28.9) | 138 (29.1) | 68 (30.1) | 70 (28.1) |

| Education level | ||||||

| No or less than primary | 163 (42.1) | 28 (38.9) | 135 (42.8) | 202 (42.6) | 80 (35.4) | 122 (49.2) |

| Primary | 94 (24.4) | 23 (31.9) | 71 (22.6) | 116 (24.5) | 61 (26.9) | 55 (22.2) |

| Secondary | 108 (27.9) | 15 (20.8) | 93 (29.5) | 134 (28.3) | 74 (32.7) | 60 (24.2) |

| Higher | 21 (5.4) | 5 (6.9) | 16 (5.1) | 22 (4.6) | 11 (4.9) | 11 (4.4) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married | 76 (19.6) | 14 (19.4) | 62 (19.7) | 89 (18.7) | 45 (19.9) | 44 (17.8) |

| Married/cohabiting | 261 (67.5) | 53 (73.6) | 208 (66.0) | 327 (68.8) | 160 (70.8) | 167 (67.1) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 50 (12.9) | 5 (7.0) | 45 (14.3) | 59 (12.4) | 21 (9.29) | 38 (15.3) |

| Employment | ||||||

| Self-employed/formally employed | 229 (59.2) | 49 (68.1) | 180 (57.1) | 289 (60.9) | 149 (65.9) | 140 (56.5) |

| Unemployed/retired | 115 (29.7) | 15 (20.8) | 100 (25.8) | 138 (29.1) | 56 (24.8) | 82 (33.1) |

| Non-paid/student/homemaker | 42 (10.9) | 8 (11.1) | 34 (7.6) | 47 (9.9) | 21 (9.3) | 26 (10.5) |

| Behavioral and psychological | ||||||

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Never drank | 91 (23.5) | 11 (15.3) | 80 (25.4) | 116 (24.4) | 50 (22.1) | 66 (26.5) |

| Drank | 296 (76.5) | 61 (84.7) | 235 (74.4) | 259(75.6) | 176 (77.9) | 183 (73.5) |

| Recent suicide attempt | ||||||

| No | 334 (86.3) | 63 (87.5) | 271 (86.0) | 416 (88.1) | 195 (86.7) | 221(89.5) |

| Yes | 50 (12.9) | 9 (12.5) | 41(13.0) | 56 (11.9) | 30 (13.3) | 26 (10.5) |

| Advised to quit | ||||||

| No | 315 (81.4) | 144 (76.2) | 171 (86.4) | |||

| Yes | 72 (18.6) | 45 (23.8) | 27 (13.6) | |||

| Attempt to quit | ||||||

| No | 198 (51.2) | 27 (37.5) | 171 (54.3) | |||

| Yes | 189 (48.8) | 45 (62.5) | 144 (45.7) | |||

| Clinical | ||||||

| Heart attack | ||||||

| No | 374 (96.6) | 68 (94.4) | 306 (97.1) | 461 (97.1) | 219 (96.9) | 242 (97.2) |

| Yes | 13 (3.4) | 4 (5.6) | 9 (2.9) | 14 (2.9) | 7 (2.1) | 7 (2.8) |

| Hypertensive | ||||||

| No | 97 (25.1) | 25 (34.7) | 72 (22.9) | 123 (79.4) | 64 (83.1) | 59 (75.6) |

| Yes | 29 (7.5) | 4 (5.6) | 25 (7.9) | 32 (16.9) | 13 (16.9) | 19 (24.4) |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | 354 (91.5) | 67 (93.1) | 302 (95.9) | 455 (95.8) | 216 (95.6) | 239 (95.9) |

| Yes | 28 (7.2) | 5 (6.9) | 13 (4.1) | 20 (4.2) | 10 (4.4) | 10 (4.1) |

Advised to quit, all variables were non-significant at the p<0.05, level except for attempt to quit. Attempt to quit, all variables were non-significant at the p<0.05 level except gender, education level and advised to quit.

b Overall number of smokers. Missing values: overall advised to quit 18.5% (88). Missing values for the overall respondents for advised to quit: age group 4.9% (19); education level 0.2% (1); employment 0.2% (1); mental illness 0.8% (3); hypertensive 67.4% (261); and diabetes 1.3% (5). Missing values for the overall respondents for attempt to quit: education level 0.2% (1) ; alcohol 21.1% (100); recent suicide attempt 0.6% (3); advised to quit 18.5% (88); and hypertensive 67.6% (320).

Characteristics of current smokers who visited a health provider

Among the 387 current smokers who visited a health provider in the past 12 months for any other medical reason, the majority were aged 18–44 years (63.3%) (Table 1). Most were men (87.1%), of rural residence (70.3%), no education or less than primary (42.1%), married/cohabiting (67.5%), and self-employed/formally employed (59.2%). In terms of comorbidities, 3.4% had a history of heart attack, 7.5% had hypertension, and 7.2% had diabetes mellitus. Recent suicide attempt and alcohol consumption was reported in 12.9% and 76.5% of smokers who visited a healthcare provider, respectively. Only 18.6% of current smokers who visited a health provider in the past 12 months for any other medical reason, reported receiving smoking advise (Figure 1).

Factors associated with attempting to quit smoking

In univariate analysis, women and unemployed/retired occupational status were significantly associated with decreased odds of attempting to quit smoking (Table 2). In contrast, primary and secondary education level and smoking cessation advise were significantly associated with increased odds of attempting to quit smoking. In adjusted analysis, being advised to quit was associated with increased odds of attempting to quit (OR=2.84; 95% CI: 1.11–7.25).

Table 2

Factors associated with quit attempts among adult smokers in the general population, WHO-STEPS Survey 2017, Zambia

| Factors | OR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–29 (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30–44 | 0.17 (0.46–1.14) | 0.16 | 1.19 (0.41–3.43) | 0.75 |

| 45–59 | 1.11 (0.68–1.83) | 0.68 | 0.88 (0.83–2.71) | 0.83 |

| 60–69 | 0.53 (0.27–1.03) | 0.06 | 0.56 (0.13–2.48) | 0.44 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Women | 0.45 (0.25–0.80) | 0.00 | 0.54 (0.19–1.54) | 0.25 |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural (Ref.) | 1 | ¶ | ¶ | |

| Urban | 1.10 (0.74–1.64) | 0.64 | ¶ | ¶ |

| Education level | ||||

| None or less primary (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Primary | 1.7 (1.06–2.68) | 0.03 | 1.04 (0.37–2.94) | 0.94 |

| Secondary | 1.9 (1.21–2.92) | 0.00 | 1.36 (0.51–3.64) | 0.54 |

| Higher | 1.53 (0.63–3.68) | 0.35 | 0.84 (0.22–3.21) | 0.80 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married (Ref.) | 1 | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 0.94 (0.59–1.49) | 0.79 | ¶ | ¶ |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 0.54 (0.27–1.06) | 0.07 | ¶ | ¶ |

| Employment | ||||

| Self-employed/formally employed (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Unemployed/retired | 0.64 (0.43–0.97) | 0.03 | 1.35 (0.53–3.47) | 0.53 |

| Non-paid/student/homemaker | 0.76 (0.41–1.41) | 0.38 | 1.35 (0.40–4.55) | 0.63 |

| Behavioral and psychological | ||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Never drank alcohol (Ref.) | 1 | |||

| Drank alcohol | 1.27 (0.83–1.94) | 0.27 | ¶ | ¶ |

| Recent suicide attempt | ||||

| No (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.31 (0.75–2.29) | 0.35 | 1.03 (0.31–3.37) | 0.53 |

| Advise to quit | ||||

| No (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.97 (1.17–3.35) | 0.01 | 2.84 (1.11–7.25) | 0.03 |

| Clinical | ||||

| Heart attack | ||||

| No (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.11 (0.38–3.20) | 0.85 | 3.29 (0.30–35.6) | 0.33 |

| Hypertensive | ||||

| No (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.63 (0.28–1.39) | 0.25 | 0.69 (0.27–1.84) | 0.47 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No (Ref.) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.10 (0.45–2.71) | 0.83 | 1.59 (0.44–5.25) | 0.44 |

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to estimate the proportion of current smokers in Zambia who receive smoking cessation advise from their healthcare providers, and to estimate the prevalence and factors associated with quit attempts. Overall, 18.6% of current smokers who attended primary healthcare facilities in Zambia in the last 12 months received advise to quit smoking by the healthcare providers. Less than half (47.6%) of the current smokers included in the analysis attempted to quit smoking. Our study has also shown that current smokers who visited a health provider in the past 12 months for any other medical reason, were more likely to quit smoking than those who did not receive the smoking advise.

Only 18.6% of smokers who attended primary healthcare facilities in Zambia in the last 12 months received advise to quit smoking by the healthcare providers. This estimate is lower than what was obtained in South Africa (29.3%)27, Taiwan (28.2%)9, and China (64%)28, as well as in the USA where the receipt of quit advise ranges from 21.2% to 51.9%14. The reasons why the estimates are low in Zambia have not yet been documented, however, from other studies, insufficient training, lack of guidelines, time29, and incentives9 have been cited as plausible factors. With the steady increase in NCDs in the Sub-Saharan region, and in Zambia in particular, healthcare providers are well positioned to use every patient contact as an opportunity for screening, cessation advise, and treatment of smokers, guided by the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) guidelines30. The overall percentage of smokers making quit attempts in this population was 47.6%. This figure was slightly lower than what has been reported previously in Sub-Saharan Africa countries including South Africa31, Kenya, and Nigeria32, yet remains notably higher than countries such as Uganda32, Japan33 and the United States34. It is, however, not expected that the percentage of those who quit smoking would be higher since the proportion of smokers advised to quit smoking in Zambia is low. It’s worth noting that for those who were advised to quit smoking and attempted to quit smoking, almost 12% and 13% attempted suicide in the past 12 months respectively, further studies are needed to establish the cause, especially in patients seeking healthcare.

In our study, even after adjusting for social demographic, behavior and psychological, and clinical factors in both models, advise to quit smoking was a statistically significant factor associated with quit attempts. This is consistent with several studies demonstrating that the healthcare provider has an important role to play in eliciting quit attempts among smokers13. Research has shown that smokers who receive quit advise and smoking cessation support from their healthcare providers are more likely to attempt to quit smoking and be successful with quitting over a very long period of time13,35. Despite this strong evidence, there have been no guidelines on how to identify, advise to quit, and treat smokers in Zambia. The current study highlights the need for a policy in Zambia that routinely identifies and advises smokers who attend healthcare facilities to quit smoking. Though not specifically evaluated in this study, it stands to reason that smokers would benefit from a policy that also recommends routine smoking cessation treatment. This calls for an emphasis on the Zambian government to fast track the capacity building of healthcare workers on smoking cessation services as recognized in the tobacco control action.

Despite the association between cardiovascular diseases and other metabolic conditions such as diabetic mellitus and hypertension not reaching statistical significance in our study, studies have shown that current smokers who are diagnosed with cardiovascular diseases and other metabolic conditions such as diabetic mellitus and hypertension are more like to quit smoking36. One possible explanation is that current smokers diagnosed with these disorders may be more motivated to quit smoking.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, we were unable to assess changes in variables over time. This being a cross-sectional design, we were only able to identify factors associated with quitting smoking and were unable to address causality. Second, although we adjusted for known confounders in the multivariable model, the potential for residual confounders inherent in observational studies remains and might have affected study outcomes. Third, the data are based on self-reported responses, which might have resulted in information bias related to misclassification of tobacco smoking and comorbidities. Fourth, we were unable to capture nuance (or spectrum) of some variables, such as alcohol use and recent suicide attempts. In addition, the dataset had limited variables to establish the correlates of the healthcare provider’s advise. Finally, the current study may have limited generalizability to other national or international settings. Nevertheless, our study, however, had the advantage of standardized questionnaires that enabled evaluation of NCD risk factors, including tobacco smoking, in Zambia.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study has shown that few smokers in Zambia are advised to quit smoking during encounters with healthcare providers. The study also found that quit advise offered by healthcare providers was significantly associated with quit attempts of the smoker. This underscores the need to strengthen smoking cessation policies that encourage routine screening, quit advise, and treatment of the smokers, so as to reduce tobacco-related comorbidities.