INTRODUCTION

Smoking among adolescents is a major public health issue1. More than 80% of smokers begin smoking before the age of 20 years2. School-based interventions aimed at reducing smoking can be an effective measure as they reach the target population, and both the intervention and outcome can be measured effectively. The school-based interventions can aim at preventing3 and/or reducing smoking4.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) designed the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS). This survey is used globally to measure the worldwide burden of tobacco among school students aged 13–15 years5. Recent findings of this survey revealed that the global prevalence of cigarette smoking among boys is 11.3% and for girls is 6.1%6. In Europe, the prevalence of smoking among adolescents (15–16 years) declined from 36% in 1999 to 22% in 20157. Smoking prevalence declined by more than 50% in Ireland, and 35% in Finland, and Sweden, whereas Italy, Croatia, and Slovakia experienced a slight decrease of about 3% to 6%7,8. The prevalence of smoking among adolescents in England declined by 11% in 2016 from 17% in 1998 to 6% in 20169. The smoking prevalence in the US also experienced a decline from 15.8% in 2011 to 8.1% in 201810. The developing world is experiencing an increase in tobacco consumption at the rate of 3.4% per annum11 while it is stable or declining in the UK, the US, and Europe7-10.

There is a range of interventions to control smoking. Globally, policy-level intervention is effective in reducing smoking compared to other interventions12-14. The success of an intervention is largely influenced by political commitment15. Leaders can be advocates and influence both the public and private sectors. School-based interventions are advocated largely to achieve a wider decline in smoking rates in larger population groups.

School-based educational interventions are mainly of five types3. These are information-only curricula, social competence curricula, social influence curricula, combined social competence, and social influence and multimodal programs. The information-only curriculum focuses on correcting inaccurate beliefs and perceptions of smoking. The social competence curriculum includes interventions in developing refusal skills by developing coping skills, self-assertiveness, and problem-solving skills. The social influence curriculum comprises interventions that teach adolescents to become aware of the influences encouraging substance use and resist offers for smoking and deal with high-pressure situations. A combined curriculum comprises both aspects of social competence and social influence. The multimodal approach involves family and community, along with school-based interventions.

Previous reviews have already examined the effectiveness of school smoking interventions in preventing smoking3,16, but little is known about the effectiveness of school-based interventions in reducing smoking. Some reviews have examined the reduction in smoking, but this has been limited to pharmacological intervention and policies, and largely among adults17,18. Thus, this study aimed to conduct a review of a school-based smoking intervention to determine its effectiveness in reducing smoking among secondary school students. The review question is: ‘Are school-based interventions effective in reducing smoking among secondary school students?’.

METHODS

This systematic review was prepared following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)19 and the findings are synthesized following the Systematic Review without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) extension20. This review was not registered.

Search strategy

The database search was conducted in two phases. The initial search was limited from 1 January 2020, until 31 December 2020. The search was updated until 15 June 2025 to include recent relevant studies. In both phases of search, CINAHL, Medline and PsycINFO databases were searched. The search was guided by the Population, Intervention, and Outcome (PIO) element of the review question. The detailed search strategy is available in Supplementary file S1. The actual search phrase used was (student* OR adole* OR child* OR teen) AND (class OR school* OR teach*) AND (prevent* OR cessation) AND (smoking OR tobacco OR cigarette) AND (intervention OR program* OR campaign OR trial OR evaluation OR experiment).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were selected for eligibility based on PIO criteria. School-based interventional studies conducted over the last 20 years, with study participants described as secondary or high school students who smoke cigarettes and report smoking reduction as the outcome, were included. In terms of exclusion criteria, those studies that have a smoking intervention linked to other types of intervention, like alcohol or multiple components, were excluded as the combined intervention may produce biased results. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded. Process evaluation and protocols were excluded as they do not discuss the study findings. Articles other than the English language were excluded

Study selection

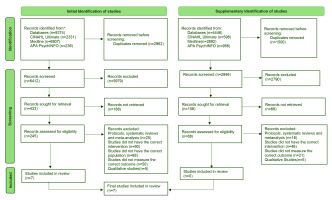

The final articles obtained from the database search were exported to Zotero, which were then verified and merged to remove duplicates. Two reviewers independently screened the articles titles, abstracts and full text using pre-defined eligibility criteria to determine whether the studies were eligible to be included in the review. Discrepancies between reviewers was resolved through discussion. The reasons for removing articles that required full-text screening were documented and presented in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

Risk of bias assessment

Quality appraisal of the evidence for the randomized controlled studies were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias-2 (ROB-2) tool21. A risk of bias table is presented below (Table 1). Cluster randomized controlled trials were also appraised using the same tool by evaluating additional domains that account for clustering. All studies’ risk of bias was independently assessed by two reviewers.

Table 1

Risk of bias

| Study Year | Selection bias | Performance bias (blinding of participants bias) | Detection bias (blinding outcome assessment) | Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) | Reporting bias (selective reporting) | Other bias (external validity) | Overall bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random bias | Allocation bias | |||||||

| Brinker et al.22 2005 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | High |

| Lisboa et al.28 2019 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | High |

| Campbell et al.23 2008 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Gorini et al.24 2014 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Jøsendal et al.26 2005 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| La Torre et al.25 2010 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Valdivieso López et al.27 2015 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | High |

Data extraction and synthesis

The Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) guideline was used to enable the transparent reporting of the review findings20. Studies were grouped as per study characteristics, population, intervention, and outcome measures used. Odds ratios (ORs) were used as a standardized metric to determine the effect sizes and direction of effect. As the meta-analysis was not feasible due to substantial clinical and statistical heterogeneity, the outcome effects were synthesized by vote counting based on effect direction. The ROB-2 tool was used to determine the study priority while synthesizing study results and drawing conclusions.

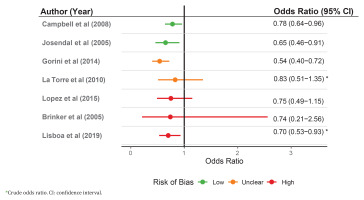

The studies were assessed for heterogeneity to examine if a meta-analysis would be feasible to determine the summary effect of an intervention. There was profound variation in age (range: 11–21 years), intervention duration (range: 1.5–19 hours), attrition (<2% to 42.5%), outcome definition (any smoking vs daily smoking) and follow-up time (12 months to 48 months) within the studies, signifying that the calculation of the average effect would not represent the true effect of an intervention. Thus, it was decided not to conduct a meta-analysis. A forest plot visually demonstrates the direction of effect ordered by risk of bias and intervention intensity (Figure 2).

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers. Data were collected in a data extraction form under the following headings: author, year of publication, country, study design, intervention details, deliverer, participant details (age, classes, number of students, and clusters), comparison group, follow-up period, and outcome measurement and validation. The studies were ordered based on risk of bias and duration of intervention, allowing comparison across groups, thereby promoting transparency (Table 2).

Table 2

Study characteristics

| Study Year Country | Design | Intervention name and core components | Delivery method | Target age (grade) | Students Clusters | Comparison group | Follow-up period | Outcome measurement and validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell et al.23 2008 UK | Cluster randomised controlled trial | ASSIST Informal diffusion outside the classroom with trained peers for 10 weeks Training of influential students for 2 days. Peer supporters logged interactions in diaries. Delivered across one school year | Trained peer-led | 12–13 (8) | 10730 59 schools | Usual education | 24 months | Self-reported anonymized questionnaire For validation, salivary cotinine was assayed in a 39% subsample at 2-year follow-up. High concordance with self-report |

| Jøsendal et al.26 2005 Norway | Two-factorial design | BE smoke FREE Classroom-based over 3 years Grade 7: 8 hours Grade 8: 5 hours Grade 9: 6 hours Based on the social influence model Included teacher training and parental involvement. | Trained teachers and parental involvement | 13 (7) | 4441 99 schools | Usual education | 33 months | Self-reported anonymized questionnaire, no validation reported |

| Gorini et al.24 2014 Italy | Clusterrandomised controlled trial | Luoghi di Prevenzione (LdP) Multi-component, delivered across one school year: 4-hour ‘Smoking Prevention Path’ workshop. 2-hour in-depth classroom lesson. Peer-led sessions (two 2-hour meetings). Teacher training and school policy enforcement. | Trainedp peer-led along with teachers’ involvement and school policy | 14–15 (1st class secondary) | 989 13 schools | No intervention | 18 months | Self-reported anonymized questionnaire, no validation reported |

| La Torre et al.25 2010 Italy | Randomised controlled trial | Skills-Based Prevention Program 5-session curriculum Health facts & short-term effects of smoking Analysis of social pressures to smoke Refusal skills training | Trained teachers | 14–15 (9) | 308 15 classes | No intervention (no contact until final assessment) | 2 years | Self-reported questionnaire, no validation reported |

| Valdivieso López et al.27 2014 Spain | Cluster-randomized controlled trial | TAB_ES Program 7 educational modules (9 sessions over 3 years) Workshops: role-playing, debates, ‘smoking machine’ Community events & parent engagement | Primary care nurses | 12–15 (1st to 4th year of CSE*) | 2245 29 schools | Assessment only (questionnaires + CO oximetry, no intervention) | 4 years | Self-reported questionnaire, biochemical validation with exhaled carbon monoxide level via oximetry |

| Brinker et al.22 2017 Germany | Randomised controlled trial | Education Against Tobacco (EAT) Photoaging activity for every student Two 60-minute interactive modules; Delivered in one day | Trained medical student-led | 11–15 (6–8) | 1504 74 classes | Usual education | 12 months | Self-reported anonymized questionnaire, no validation reported |

| Lisboa et al.28 2019 Brazil | Randomised controlled trial | Education Against Tobacco (EAT) Single 90-minute session ‘Smokerface’ facial photo-aging mobile app Gain-framed, interactive mentoring on smoking effects | Trained medical student-led | 12–21 (7–11) | 2348 110 classes | No intervention (no contact until follow-up assessments) | 12 months | Self-reported questionnaire, planned but failed biochemical validation due to systemic refusals |

RESULTS

The search was conducted in two phases. There were 9374 and 4446 records identified in the initial and supplementary identification of studies. Following screening (Figure 1), 7 studies were considered eligible for inclusion in the review.

Study characteristics

Six studies were conducted in Europe (one in Germany22, one in England and Wales23, two in Italy24,25, one in Norway26, and one in Spain27) and one study was conducted in Brazil28.

Four of the studies were cluster-randomized controlled trials23,24,26,27 and three were randomized controlled trials22,25,28. In the cluster-randomized controlled trial, the unit of randomization was a school, as a whole school and its students were either in the intervention group or in the control group while in the randomized controlled trial, either class was a unit of randomization25 or individual students were randomly assigned to intervention group or the control group22,28. The detailed study characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Quality appraisal

Three out of seven studies were assessed as high risk of bias22,27,28 (Table 1). All of the studies were assessed low risk of random bias, except Gorini et al.24, as three control schools refused their allocation and were moved to the intervention group, potentially resulting in a selection bias. While La Torre et al.25 did not provide detailed information on how the participants were randomly assigned, Valdivieso López et al.27 had imbalances in baseline characteristics (school type, socioeconomic status, and immigration status) among the participant group, both assessed as unclear allocation bias.

In addition, Brinker et al.22 , Lisboa et al.28 and La Torre et al.25 were assessed to have unclear performance bias as both the intervention and control groups were in the same school. Teachers were involved either in the delivery of intervention and/ or the administration of outcome surveys, and assessed as unclear performance bias in Campbell et al.23 and Jøsendal et al.26. Gorini et al.24 assessed as unclear performance bias, as only two out of six schools implemented anti-smoking policies, one of the core components of intervention.

In all of the studies, the outcome was dependent on self-reported data and was assessed as unclear detection bias, except Campbell et al.23 and Valdivieso López et al.27 who performed biochemical validation and were assessed as low risk. The average attrition rates in Brinker et al.22, Lisboa et al.28 and Valdivieso López et al.27 were 52.26%, 42.38%, and 29.5% respectively, and assessed high attrition bias. Gorini et al.24 was assessed unclear attrition bias (about 23%), similar in both groups.

All the studies had a pre-specified plan/protocol for reporting the primary outcome, so they were assessed to have low risk of reporting bias. Other biases include threatened external validity in Brinker et al.22 by higher attrition and potential sample contamination, while with post-randomization selection bias in Gorini et al.24. The significant effect of ASSIST trial23 in a close-knit Welsh valley, the strong effect of the Norwegian program26 associated with a supportive national context, may not exist in other settings. The effect of a study conducted in public schools by Lisboa et al.28, a tobacco-producing region by La Torre et al.25 and a major economic crisis in Spain27 may be different in other situations, thus limiting the external validity of the studies.

Study participants and characteristics

Two studies recruited participants via mobile application22,28. Five studies invited schools in a specific region to participate in the study all the students from selected classes were chosen for the study23-27. Grade 7 was the most common level studied.

Campbell et al.23 conducted study among the secondary schools in Southeast Wales and the West of England, where grade 8 students participated in the program. Among the 223 schools invited, 59 randomly selected schools agreed to participate in the study. Among them, 29 schools (5372 students) were assigned to the control group, and 30 schools (5358 students) were in the intervention group. The intervention was delivered by the most influential peers in grade 8 who were recruited by the students’ nomination23. The intervention group consisted of 95% (5074) of participants at baseline, and 90% (4763) at the end of 2 years of follow-up. For the control group, 97% (5187) participated in baseline data collection, and 94% (4984) participated at the end of the 2-year follow-up. The differences in baseline characteristics of participants on smoking status (control: 6.6% vs intervention: 4.8%, p-value not given, but deemed significant) were adjusted using statistical models by the authors.

Jøsendal et al.26 included national representative schools in Norway, and grade 7 students participated; 99 schools (4441 students) were randomly assigned to four groups, i.e. three intervention groups (classroom curriculum, teacher-course and parental involvement, classroom curriculum and teacher course, classroom curriculum, and parent involvement) and one control group. The group consisted of 25 schools, each with a comparable student size. At the end of the 3-year study period, there was an 11.2% and 5.8% loss to follow-up in the intervention and control groups, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in smoking habits among the study groups. The authors did not report data on demographic characteristics.

Gorini et al.24 invited secondary schools in Reggio Emilia province that have not previously participated in the school-based smoking program, and participants were students in the first class of secondary school. Out of 20 schools invited to participate, seven schools violated the protocol, and the remaining 13 schools were randomized. Six schools (1025 students) were allocated to an intervention group and seven schools (1104 students) to the control group. In the intervention group, 80.0% (488 students) completed both baseline and 18-month post-intervention follow-up. In the control group, 76.4% (501 students) completed both baseline and post-intervention follow-up. There were statistically significant differences in the baseline characteristics of participants, gender (52.1% girls in the control vs 35.9% in the intervention, p<0.001) and school type (12.2% vocational schools in the control group vs 5.1% in the intervention group, p<0.001), but were handled by authors using multilevel regression models and propensity score matching.

La Torre et al.25 involved high schools in Frosinone Province, Italy, and grade 9 students participated; 15 classes (308 students) of Scientific and Classic Licea were recruited in the study. Among them, 8 classes (162 students) were assigned to an experimental group and 7 classes (146 students) were assigned to the control group. At the end of the 2-year follow-up, there were 160 and 144 participants in the experimental and control groups, respectively. Only 2 cases were lost to follow-up in both groups. There were no statistically significant differences in baseline and demographic characteristics between study groups.

Valdivieso López et al.27 involved all secondary schools in the Catalan Province of Tarragona, Spain, and students in the first year of secondary school participated. Of 2663 students from 29 schools assessed for eligibility, 418 students were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria; 15 schools (1156 students) were assigned to an intervention group, and 14 schools (1089 students) were assigned to a control group. At the end of 3 years of follow-up, there were 67.4% (779) students in the intervention group and 73.8% (804) students in the control group. There were statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics of participants in socioeconomic status, school type, and immigration status that were accounted for by the authors using multilevel logistic regression models.

Brinker et al.22 recruited grade 6 to 8 students attending secondary schools in Germany. All 1504 participants were eligible and were randomized on the class level within each school. There were 40 intervention classes and 34 control classes. All the participants participated in a one-time intervention. At the end of a 1-year study, 718 participants provided the data. The attrition rate was 52.26%. There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics among the study groups.

Lisboa et al.28 recruited students from grades 7 to 11 attending public secondary schools in Brazil; 2348 students were eligible to participate and were randomized on the class level within each school in 14 schools. All the participants participated in a one-time intervention. At the end of a 1-year study, 1353 participants provided the data. There was a higher baseline smoking prevalence in the intervention group (14.1%) compared to control group (11.0%). The authors used GENLINMIXED to adjust for the differences in age and academic performance, but it is not stated whether they performed an adjustment for baseline smoking status.

Intervention

All the studies were delivered in school in a classroom setting. Campbell et al.23 conducted a peer-led intervention that lasted for 10 weeks. They trained influential peers in school using roleplays, student-led research, group discussion, and games. Peer supporters engaged in informal communication with peers about the hazards of smoking and the benefits of remaining smoke-free as well as developing strong behavioral skills to deny smoking.

Jøsendal et al.26 had three intervention groups; one was comprehensive involving classroom curriculum, teacher-course, and parents and the other two groups did not have either teacher or parental involvement. It consisted of 8, 5, and 6 sessions of 1 hour each delivered over three years, respectively.

Gorini et al.24 conducted an intervention based on four components. It comprised the out-of-school workshop (lab session, computer session, creative writing session, imaginative session) for four sessions of 40 minutes each, a two-hour in-depth classroom session, three sessions of peer-led intervention each lasting for two hours, and school anti-smoking policy. The program was delivered for 1 year by trained teacher.

La Torre et al.25 focused on the curriculum in developing students’ refusal capability of cigarettes. It consisted of three sessions of two hours each and two appointments with the teacher. It was delivered by the schoolteacher.

Valdivieso López et al.27 focused on workshops and in-classroom sessions, delivered by trained nurses in collaboration with class teachers. It consisted of 3 sessions of 1 hour each delivered in a year over three years.

Brinker et al.22 applied the 2014 version of the ‘Education Against Tobacco’ curriculum. It consisted of two sessions of one hour each delivered in one day by trained medical students. There were two parts to the intervention. Firstly, a PowerPoint presentation in class relating to the benefits of avoiding smoking on topics like physical performance, addiction versus freedom. The second part was a classroom seminar and an aging intervention of the participant’s selfie through morphing software, which produced 2D images referred to as photoaging.

Lisboa et al.28 applied the most recent ‘Education Against Tobacco’ curriculum. It has one session of 90 minutes delivered in a classroom over one day by trained medical students. It consisted of four stations. In the first station, students discuss and experiment with the harmfulness of cigarettes, the second consisted of an intervention of the participant’s selfie through an updated app that produced 3D images of ageing (photoaging application), third was an interactive session on the benefits of non-smoking and harmful effects of smoking and fourth was on discussion of students’ own experience with tobacco.

Outcome measurement

Six studies collected data on sociodemographic characteristics22-25,27,28 and one did not collect data on the sociodemographic component26. Jøsendal et al.26 collected data on one question regarding the frequency of smoking. All the studies except Campbell et al.23 and Valdivieso López et al.27 relied on self-reported quitting data.

In Campbell et al.23, the students in intervention schools had 78% odds of smoking compared to the control group, statistically significant effect (adjusted odds ratio, AOR=0.78; 95% CI: 0.64–0.96). The authors reported the primary outcome as a multilevel model combining data from all follow-up periods.

In Jøsendal et al.26 at three years follow-up, students in the intervention group had 65% odds of smoking compared to the control group (daily or weekly smoking collapsed into a binary variable) (AOR=0.65; 95% CI: 0.46–0.91). The two intervention groups, which did not involve either parents or teachers, were less effective than the comprehensive intervention. After adjusting for age and gender, the likelihood of becoming a smoker in the intervention group was significantly lower (Wald’s=9.81, degree of freedom (df)=3, p=0.020) compared to the control group.

In Gorini et al.24 at the eighteen-month follow-up, the odds of daily smoker among intervention group was 54% the odds in control group (OR matched on propensity score=0.54; 95% CI: 0.40–0.72), statistically significant effect.

In La Torre et al.25 at two-year follow-up, the odds of smoking in the intervention group was 83% compared to the control group (OR=0.83; 95% CI: 0.51–1.35), statistically insignificant. The authors did not distinguish smoking frequency among participants or the timeframe to measure smoking habit.

In Valdivieso López et al.27 at four-year follow-up, the odds of smoking in the intervention group was 75% the odds in the control group (daily and occasional smoking combined to report binary smoking variable), statistically insignificant (AOR=0.75; 95% CI: 0.49–1.15).

In Brinker et al.22 at one-year follow-up, the odds of current smoking in the intervention group was 74% the odds in the control group (binary outcome), statistically insignificant (AOR=0.74; 95% CI: 0.21–2.56).

In Lisboa et al.28 at 12 months follow-up, the students in the intervention group were 30% less likely to smoke (binary outcome), statistically significant (OR=0.70; 95% CI: 0.53–0.93). The authors defined smoking, including multiple tobacco products (e-cigarettes, waterpipe), and presented findings on baseline smoking characteristics and the change in smoking prevalence, demonstrating the actual effect of an intervention.

DISCUSSION

Four out of seven studies were effective in reducing smoking prevalence23,24,26,28. The duration of an intervention is an important factor in determining its effectiveness in reducing smoking. Within the interventions, there was variation in the overall length (one to three years) and duration of sessions (one to two hours). Most of the effective interventions were conducted either over a longer period or multiple sessions, or both, which is consistent with the meta-analysis findings29,30, except the study by Lisboa et al.28 who conducted only one session of 1.5 hours (high risk of bias), suggesting that the use of a highly novel and engaging intervention (photoaging application) can be effective even with a brief intervention. Whilst, previous reviews have recommended that the duration of a three-year school smoking program be delivered either at least five sessions per year over two years29 or at least 10 sessions over eight to twelve weeks30, the novel approaches could demonstrate promising results even with a brief intervention. Thus, future studies should consider the use of the photo morphing application or software in smoking intervention, particularly among adolescents, which creates plausible psychological concerns about physical appearance and could impede smoking behaviour31.

Effective school-based smoking reduction interventions require interactive delivery of the intervention. Though all the studies delivered knowledge face-to-face, the effective interventions applied interactive methods23,24,26-28. These included peer interaction23,24 (low risk of bias), use of photoaging software22,28, small group discussion28, parent and family26, and the community27. The involvement of families and communities in the project is considered an interactive method in program delivery32. Ineffective interventions applied the non-interactive method22,25. The delivery of the intervention was largely unidirectional in the form of a PowerPoint presentation22, and classroom teaching25. A previous study has found non-interactive methods to be either ineffective or less effective compared to the interactive methods33, similar to this review’s findings.

Effective school-based smoking interventions require trained individuals, irrespective of profession, to deliver the school-based smoking program. All the interventions were delivered by individuals who had received training on the intervention. There was no difference in the effectiveness of the intervention when it was delivered by professionals, a school teacher16, a medical student15, and a nurse in collaboration with a schoolteacher27. Effective interventions were also delivered by trained medical students17, school teachers20,21, and peers23 (low risk of bias). However, a review34 has found that peer-led interventions are more effective compared to the teacher or researcher delivery of the intervention in the smoking prevention programs among secondary school students.

The curriculum of the school-based smoking program should include a multicomponent intervention. All of the interventions had either a practical and/or cognitive component along with a knowledge component, but they primarily focused on the knowledge-based component. Previous reviews have revealed that a knowledge-based program has a relatively smaller effect on attitude and behavior changes3, so is a curriculum based only on practical skills, which is not effective in reducing smoking3,35. Additionally, interventions with both practical and cognitive components were found to have a better outcome3,33,36,37 compared to the studies with a cognitive component only3,38,39. Several studies have found parental and family involvement3, community involvement40, school antismoking policies41 an effective component of school smoking programs. These components help to strengthen the school-based smoking intervention by broadening the context of the program and increasing the influence and impact of the message, hence can help reduce smoking among students.

In this review, we were unable to determine the effectiveness of each component of an intervention due to the diverse intervention components in the chosen studies. Historically, there were some proposals42,43 to study these components but they have not been studied and hence the effect of specific components is still not known44-46. It was also not possible to conduct subgroup analyses as studies reported limited data on baseline characteristics of participants. There is a need for future studies to assess whether individual components of a school-based smoking program are effective, or to examine the comparative effectiveness of those components in reducing smoking among students.

Strengths and limitations

The search was limited to articles published in the English language and the limited database only. This could have resulted in the omission of relevant studies and articles published in other languages. The studies published in other languages could have been missed, and a grey literature search was not carried out, leading to a publication bias. The studies relying on self-reported smoking behavior were considered to have a high risk of detection bias; however, a study47 found that the validity of self-reported smoking status was high, with a sensitivity of 90%, suggesting that detection bias may not be at high risk. GRADE assessment could not be undertaken due to the substantial heterogeneity in outcome definition and statistical reporting of the studies.

One of the major strengths of our study is transparency and the use of appropriate guidelines. We have used the PRISMA and SWiM guidelines and synthesized our findings, prioritizing the study quality. Another strength of this study is the addition of information on a smoking reduction program based on a photoaging software app. The extensive reviews3,48 published previously lack findings on the effectiveness of application-based school smoking interventions, which are added by this review. We acknowledge that there were limited studies based on photoaging application in this review, and the findings should be treated with caution; however, extensive studies on this arena could potentially result in favor of interventions resulting in cost-effective implications for school-based smoking programs, given that these interventions are brief and have delivered promising results.

Smoking among adolescents is a significant public health problem, and this review synthesizes and summarizes the available data on the topic. Although the included studies were conducted at different times ( 2005 vs 2019) and the countries were at different stages of the cigarette epidemic, youth smoking prevalence was similar across countries, enhancing the validity and comparability of the findings. Since then, youth smoking prevalence has declined substantially, and the same interventions may not achieve the effects observed in earlier, higher-prevalence contexts. Nevertheless, the review provides valuable insights into effective smoking reduction strategies, which can guide the development of more targeted and intensive interventions for contemporary low-prevalence settings.

Recommendations

Effective school-based smoking programs should include a multi-component intervention, ensuring interactive delivery by a trained individual. There is a huge variation within the components of the school-based smoking programs; thus, future studies could take this into account and design a standard intervention for a particular component, which would make it easier to determine the effectiveness of components and conduct a comparative study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study synthesized existing school-based interventions to determine their effectiveness in reducing smoking among students. The results of this review suggest that school-based interventions demonstrate a beneficial effect towards smoking reduction. However, the results of this review should be treated with caution based on study quality.