INTRODUCTION

Smoking remains one of the most widespread preventable causes of disease and death. As of 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 1.25 billion smokers worldwide, contributing to millions of annual deaths from cancer, cardiovascular disease, and chronic respiratory illness1. Despite decades of public health interventions, tobacco use continues to impose a significant burden on healthcare systems globally2.

Jordan faces a smoking epidemic, having one of the highest smoking rates, with over 40% of adults reported as current smokers3, a prevalence that contributes to tobacco-related diseases accounting for nearly 80% of all deaths in the country. This substantial disease burden translates into an estimated 9027 tobacco-related deaths annually, with 56% of these considered premature deaths4.

Although the harmful effects of smoking are well established, tobacco use remains prevalent among physicians in Jordan. This paradox has important implications for public health, as physicians who smoke may find it difficult to engage in cessation counseling and could potentially be perceived as less credible by patients. A recent review highlighted multiple factors influencing smoking attitude among health professionals, including occupational stress, lack of tailored cessation programs, social and cultural norms, and limited institutional support5. The review also noted that health professionals with substance use disorders – nicotine included – are often diagnosed and referred for treatment later than the general population, partly due to stigma and professional role expectations. These findings show the urgent need for targeted, evidence-based cessation interventions for health professionals, not only to safeguard their health but also to enhance their effectiveness in delivering smoking cessation support to patients5.

The association between occupational and psychological factors and smoking behavior among healthcare professionals has been observed in multiple settings. For example, a study in Istanbul shows a link between low mindful awareness and high psychological dependence on smoking6. Similarly, a study in Norway found that longer work hours reduced the odds of cessation due to limited access to programs7.

As future physicians, medical students’ smoking behaviors are of particular concern, as they may influence both their personal health and future patient counselling practices. A study in a Jordanian university found that 28.6% of 650 students were smokers8. One possible explanation for this high prevalence is the presence of self-exempting beliefs, whereby students believe they can mitigate the harmful effects or quit before long-term damage occurs9. Guided by the Five-Factor Model of Personality, Gender Role Theory, and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), this study examines traits identified from prior literature, including sociability (aligned with extraversion), responsibility (aligned with conscientiousness), impulsivity (reflecting low conscientiousness and high neuroticism), reflectiveness (overlapping with openness to experience), and masculinity10,11. In addition to these personality dimensions, the study also considers attitudes, perceived norms, and day-to-day lifestyle factors, such as time mismanagement, poor sleep, and exam preparation, that shape behavioral choices and may influence smoking initiation among medical students12,13. Understanding the drivers of smoking initiation among medical students is essential for designing targeted prevention strategies, as their behaviors today will shape both their long-term health and their effectiveness as future healthcare providers. This study aims to identify factors associated with smoking initiation among medical students at the University of Jordan, focusing on lifestyle, personality traits, and public health attitudes.

METHODS

Study design and sampling

This is a cross-sectional study conducted at the University of Jordan School of Medicine. Data were collected from 13 December 2023 to 15 March 2024. Inclusion criteria were: being active medical students aged 18–25 years, and enrolled at the University of Jordan. Exclusion criteria were non-medical student status, those who did not consent, those younger than 18 years or older than 25 years, or not officially enrolled at the University of Jordan. The age 18–25 years was chosen because it represents the typical age range of medical students at the University of Jordan. The sample size was determined as 360 by using the formula:

where N was 5479, which was the total number of medical students at the time of data collection, p was 50%, confidence limits 5%, and design effect 1 for a 95% confidence level.

Considering the annual variability in the distribution of students by gender and year of study (1st to 6th year), a proportionate stratified sampling approach was initially employed to ensure adequate representation across both variables. Within each stratum, participants were then recruited using convenience sampling until the predetermined quota for gender and year of study was achieved. Students were approached in the university, during break times, or during hospital rounds.

The final sample included: 1st year 83 students (Males=40 vs Females=43), 2nd year 88 students (42 vs 46), 3rd year 73 students (33 vs 40), 4th year 51 students (25 vs 26), 5th year 63 students (30 vs 33), and 6th year 36 students (16 vs 20).

Questionnaire and data collection

Data were collected from 13 December 2023 to 15 March 2024 using a self-administered questionnaire (Supplementary file Questionnaire) accessed via QR code (Google Forms). A structured questionnaire was designed, reviewed, and validated by two specialists and a senior otolaryngology resident at Jordan University Hospital. To ensure accuracy and avoid duplication, surveys were completed in person, with researchers present. The questionnaire contains 45 items across multiple sections: demographics including year, age, gender, and income; smoking behavior such as status, frequency, type, and timing of initiation; influencing factors based on yes or no responses about reasons for initiation; smoking patterns using Likert-scale responses about frequency during exams, after waking, and other situations; attitudes and personality traits associated with smoking; and knowledge about health risks, lifestyle impact, and addiction. A pilot study was conducted with 43 students (10.9% of the total sample) from across academic years and showed strong internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.846.

Three researchers approached students between lectures and clinical rotations. After introducing themselves and explaining the study, participants were invited to scan a QR code to access the consent form and questionnaire. Those who provided informed consent completed the form on their personal devices. Researchers remained available for questions during completion.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, JASP software was used14. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics like frequencies and percentages were used for categorical data. Means and standard deviations (SD) were used for normally-distributed continuous data, and medians with interquartile range (IQR) were used for non-normally distributed data, alongside box plots for selected variables. Normality of continuous variables was confirmed using histograms.

To analyze the association between different basic features of smoking, smoking daily habits, and factors that led the participant to smoke, with sex, we used Pearson’s chi-squared test, Cochrane-Armitage test for trend, and Mann-Whitney U test, each where applicable. In addition, we used multiple logistic regression analysis to find out which factors are associated with current smoking status among medical students while adjusting for potential covariates (including students’ perceptions of smokers’ personality traits, age, family income, and sex). We controlled for these factors specifically because they may be related to smoking initiation, because they were associated with smoking in the literature, and because they were the most important to be adjusted for, considering the sample size and rule of ten events per included parameter.

Regression results were presented using odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and the assumptions of the analysis, including the rule of ten events per predictor, were met. Also, the absence of multicollinearity was confirmed with all variance inflation factors (VIF) <4. Considering the mandatory frame of all of the survey questions, the data are free of missing data.

While determining which factors predict smoking in medical students, we incorporated students’ attitudes toward physician-related public health interventions for reducing smoking (which were assessed using 6 Likert items in our model, besides basic features. To ease this step, the questions related to physician-related public health interventions for smoking reduction were scaled, and the total score for the scale was included in the regression analysis as an independent predictor. To ensure the construct validity of the total scores, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted, and the reliability analysis using MacDonald’s Omega (ω) was also done. The extraction method was weighted least squares, which is suitable for the ordinal data, and it was based on a correlation matrix. As no potential correlation between factors was proposed, an orthogonal rotation (varimax) was used.

Considering that our sample is relatively small to be divided into two subsamples to conduct EFA and CFA on each, we conducted the two steps on the same sample by conducting an EFA followed by a CFA. Our approach respects the sample size assumptions of both analyses and aligns with the recommendation of Brown15, who recommended using EFA in a CFA framework. EFA followed by CFA is a common approach to scale validation.

RESULTS

Demographics

After analyzing the data, the following results were found. The total number of participants was 394, and the mean age was 20.4 years (SD=1.8). A large proportion of our study participants were either smokers or ex-smokers (29.4%), but the majority of them were males (38.6%; n=73). Table 1 further demonstrates the demographics of participants.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics and basic features of medical students participating in a cross-sectional study at the University of Jordan, 2023–2024 (N=394)

Basic smoking features and related daily habits in smokers

Our results showed that males tended to smoke at an earlier age compared to females, with a significant difference (p=0.01). Also, they tend to smoke a higher number of cigarettes daily (p=0.003). In addition, males were more likely to smoke at college (p=0.007), when they wake up (p=0.001), and at exam times (p=0.01). Supplementary file Table A1 provides detailed comparisons. Regarding the factors that contributed to smoking initiation, Table 2 shows the sex differences in starting smoking. Notably, a feeling of independence was the only significant factor associated with sex, with females being more likely to start smoking for this reason (p=0.032; 69.8% vs 49.3%).

Table 2

Self-reported reasons for smoking initiation, by sex, among medical students in a cross-sectional study at the University of Jordan, 2023–2024 (N=116)

| Reasons | Female n (%) | Male n (%) | Total n (%) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 43 | 73 | 116 | |

| Influence of friends and family | ||||

| No | 6 (14.0) | 21 (28.8) | 27 (23.3) | 0.068 |

| Yes | 37 (86.1) | 52 (71.2) | 89 (76.7) | |

| Time mismanagement + poor exam preparation | ||||

| No | 25 (58.1) | 45 (61.6) | 70 (60.4) | 0.71 |

| Yes | 18 (41.9) | 28 (38.4) | 46 (39.7) | |

| Poor sleep (<5 h/day) | ||||

| No | 26 (60.5) | 41 (56.2) | 67 (57.8) | 0.65 |

| Yes | 17 (39.5) | 32 (43.8) | 49 (42.2) | |

| Bad dietary habit + physical inactivity | ||||

| No | 19 (44.2) | 35 (48.0) | 54 (46.6) | 0.7 |

| Yes | 24 (55.8) | 38 (52.1) | 62 (53.5) | |

| Live without family | ||||

| No | 30 (69.8) | 52 (71.2) | 82 (70.7) | 0.87 |

| Yes | 13 (30.2) | 21 (28.8) | 34 (29.3) | |

| Feeling of independence | ||||

| No | 13 (30.2) | 37 (50.7) | 50 (43.1) | 0.032 |

| Yes | 30 (69.8) | 36 (49.3) | 66 (56.9) | |

| Stress relief | ||||

| No | 11 (25.6) | 22 (30.1) | 33 (28.5) | 0.6 |

| Yes | 32 (74.4) | 51 (69.9) | 83 (71.6) |

Students’ perceptions of the personality traits of smokers

We found that, based on univariate analysis, students who think that smokers are less likely to have a responsible personality trait were more likely to be non-smokers (p<0.001). Also, students who think that smokers are more likely to be impulsive were more likely to be non-smokers (p=0.025) (see Table 3, where all p-values are based on Pearson’s chi-squared test).

Table 3

Medical students’ attitudes toward personality traits that are more likely to smoke in a cross-sectional study at the University of Jordan, 2023–2024 (N=394)

Predictors of smoking in medical students: Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis results

Interestingly, due to low factor loadings, only 4 out of 6 items were retained for the scale. EFA analysis supported retaining 1 factor via scree plot, and Table 4 shows items loadings on this factor, all of which are above 0.6. In addition, the cumulative variance explained by this factor was 50%, which is acceptable. CFA also supported retaining these four items with an overall KMO of 0.77 and a significant Bartlett’s chi-squared p-value (p<0.001). Also, model fit indices were acceptable (CFI=0.99, TLI=0.98, RMSEA=0.067, SRMR=0.019), confirming model fitness. Reliability analysis using MacDonald’s Omega (ω) revealed acceptable reliability for this factor (ω=0.80). Factor 1 was attitudes toward physician-related public health interventions for reducing smoking. The median value for this scale was 17 (IQR=15–19), and there was no significant difference in total score based on sex (p=0.163).

Table 4

Factor loadings for items related to medical students’ attitudes toward physician-related public health interventions to reduce smoking in a cross-sectional study at the University of Jordan, 2023–2024 (N=394)

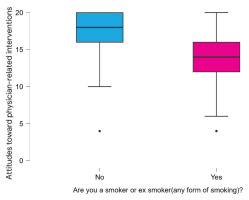

Regarding regression analysis, which was done to determine which factors predict smoking prevalence among medical students, model fit indices were acceptable (Nagelkerke’s R2= 0.447, AUC=0.862) with all VIF values <4 and the rule of ten events per predictor being met. Results showed that sex significantly predicted smoking prevalence, with males having higher odds (AOR=2.49; 95% CI: 1.42–4.37, p=0.001) as noted in Table 5. Also, higher attitude scores (i.e. better attitudes) toward physician-related public health interventions for reducing smoking were associated with decreased odds for smoking (AOR=0.64; 95% CI: 0.57–0.71, p<0.001), as noted in Figure 1.

Table 5

Multiple logistic regression results for predictors of smoking in medical students in a cross-sectional study at the University of Jordan, 2023–2024 (N=394)

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to identify predictors of smoking initiation among medical students at the University of Jordan, focusing on lifestyle factors, personality traits, and attitudes toward physician-led public health interventions. The findings reveal that smoking initiation is influenced by both pre-medical school experiences and pressures encountered during medical training, as most smokers began before entering medical school, with male students initiating earlier, smoking more frequently, and reporting higher use during college, after waking, and under academic stress, while female students more often linked smoking with a sense of independence. Non-smokers tended to perceive smokers as less responsible and more impulsive. Importantly, students overall demonstrated strong support for physician-led public health interventions, including smoking bans and cessation programs, and these favorable attitudes were associated with lower smoking rates.

The high prevalence of smoking in the Jordanian population, which is reflected among medical students, occurs within a context of entrenched social acceptance and widespread exposure, as documented in the WHO’s Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use and the Jordan Tobacco Control Investment Case1,3. The greater burden among males mirrors regional and international findings, where masculine norms often normalize risk-taking behaviors such as smoking16,17. According to gender role theory, smoking may be perceived as an expression of independence or resilience, particularly among young men; this aligns with cross-cultural evidence that smoking symbolically reinforces masculine identity18. In contrast, the link between independence and smoking among female students suggests a shift in gender norms, where smoking is framed as autonomy19. These cultural patterns may help explain the persistently high rates observed in this study.

Beyond cultural and gendered influences, day-to-day lifestyle factors also played a critical role in shaping smoking behaviors. Students reported smoking more frequently under academic stress, particularly during examinations, aligning with international evidence that medical training is a period of heightened vulnerability to unhealthy coping strategies20. Other lifestyle factors, such as poor sleep and time mismanagement, create an environment conducive to smoking initiation and maintenance. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated the prevalence of sleep problems among more than half of medical students across 31 countries21. The effect this has on smoking initiation is seen in a recent study, which followed university students over time and found shorter sleep correlated with a higher risk of smoking initiation22. In addition to sleep irregularities, academic schedules often impose time constraints, which prior reviews suggest hinder students from seeking smoking cessation support and may prompt continued tobacco use as a coping mechanism23. Within the framework of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), such stressors may reduce perceived behavioral control and increase susceptibility to social norms that normalize smoking as a coping mechanism; indeed, TPB has been shown to significantly predict smoking intentions and behavior in adolescent and university populations and perceived behavioral control and attitudes have been key predictors of smoking behavior in medical students specifically24,25. This underscores the need for medical schools to provide healthier alternatives for stress management.

An additional role is played by various personality traits. Responsibility emerged as a significant protective factor, consistent with the Five-Factor Model, where conscientiousness is associated with self-regulation and avoidance of risky health behaviors26. Impulsivity, often conceptualized as low conscientiousness and high neuroticism, has been linked to risk-taking and lower capacity for delaying gratification, explaining its association with smoking in the literature and its perception as a smoker’s trait among non-smokers27. Reflectiveness, which may be related to openness to experience, did not emerge as significant in this study, though other studies suggest it may affect decision-making in health behaviors28. These findings suggest a complex relationship between stable personality dispositions, situational stressors, and smoking behavior.

Students’ strong support for physician-led tobacco control reflects both their professional identity and public expectations – most Egyptian medical students reported positive attitudes toward tobacco control policies and expressed a desire for cessation training29. Consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior, medical students with greater tobacco education and clinical experience exhibited higher preparedness to deliver cessation counselling, suggesting that reinforcing these values during training may both reduce smoking prevalence and prepare students to counsel patients more effectively30. A widely prevalent expectation is that physicians should not smoke, which aligns with international findings and reinforces the importance of physicians as role models. To support this role-modeling function, embedding cessation counseling into the medical curriculum is supported by education-based evidence31. A meta-analysis found that tobacco dependence training improves students’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and smoking cessation interventions, while specific training courses (e.g. the Sisma Project) enhance counseling skills32.

Limitations

This study is cross-sectional, limiting causal inference. It was conducted at a single institution, though the University of Jordan’s diverse student body may enhance generalizability. The use of self-reported data potentially introduces recall and social desirability bias and creates a risk of misclassification bias regarding smoking status. Although the questionnaire was piloted and underwent exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, psychometric testing was conducted within the same sample, which may limit the generalizability of the scale. Moreover, while proportionate stratification was employed to ensure representation and minimize bias, the use of convenience sampling within strata may still have introduced selection bias and limited the generalizability of the results. Longitudinal studies are warranted to track smoking trajectories across medical training and to validate the psychometric properties of the attitude scale in broader student populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Smoking remains common among Jordanian medical students, most of whom begin after medical school. Male gender and stress during exams were identified as key factors associated with smoking behavior. Additionally, personality perceptions and student attitudes toward physician-led public health measures were significantly associated with smoking status. These findings highlight the potential benefit of early and targeted interventions that target both behavioral and psychosocial risk factors. These findings also suggest that medical schools could consider prioritizing smoking prevention and cessation programs and providing support in the areas of stress management. Addressing tobacco use during medical training may help protect the students’ health as well as strengthen their role as future healthcare professionals.