INTRODUCTION

Smoking predisposes to significant adverse effects on the oral, gingival, and pharyngeal mucosal surfaces, resulting in structural changes and atrophy1,2. In addition to the reduction in salivary flow and the decreased mucosal immunity, smoking is detrimental to the oral microflora. These changes may play a significant role in introducing more tonsillar infections3-6.

Tobacco nitrosamines are a group of inhaled toxicants involved in the etiology and induction of tumors as well as in functional and morpho-structural changes resulting in tissue injury7,8. Due to the changes caused by tobacco smoke in the oral cavity and pharynx, secondary bacterial infections of the tonsils ensue through biofilm formation in the tonsils. Biofilm represents an assembly of bacteria enclosed in an extracellular polysaccharide matrix creating an environment for augmentation of nutrient gradients, genetic exchange, and quorum sensing enabling the bacteria to survive in adverse conditions and to develop resistance. This results in chronic recurrent tonsillitis not amenable to medical treatment9,10.

Interestingly, chronic recurrent tonsillitis has both infectious and non-infectious etiologies. Viral causes which are the most common cause, encompass rhinovirus, coronavirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, Coxsackie virus, bocavirus, and metapneumovirus11,12. Group A streptococcus is the most common bacteria to cause sore throat, accounting for approximately 15–30% of cases in children13. Besides these, there are other non-infectious causes of the sore throat like snoring, voice abuse, drug-induced from inhaled corticosteroids, and concomitant illnesses like quinsy, Kawasaki disease, Kikuchi disease, periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome, recurrent IgA vasculitis, inborn errors of immunity, and laryngopharyngeal reflux disease14. A sore throat may result in the infection of the tonsils, adenoids, eustachian tube orifice, posterior pharynx, uvula, and soft palate. Infection and inflammation over these areas will be perceived as sore throat. The soreness will increase on chewing and swallowing, as inflamed tissues are physically stretched and glide over one another during this process15. Therefore, a positive history of sore throat always does not include tonsillitis.

The Surgeon General’s Report in 2006 on secondhand cigarette smoking concluded that for secondhand smoke, there are no lower cutoff values of safe level of exposure16. Literature supports that thirdhand smoke from cigarette residues can also expose children to toxins17,18. Smoking is a known factor of harm on the innate immune system, leading to impaired resistance to usual upper respiratory infections, e.g. otitis media19. There are very few studies elaborating the impact of secondhand smoke leading to upper respiratory tract infections. In the South Asian context, there are very few studies explaining the relationship between secondhand smoke and chronic recurrent tonsillitis. Our study evaluates the association of secondhand smoking as a risk factor for increasing the chance of both infectious and non-infectious tonsillitis. To add to the available data on human tonsils functional and morphological analysis, our case-control study explores and estimates the adverse effects of secondhand cigarette smoke at home on both epithelial and non-epithelial tonsillar compartments of children with histopathological analysis.

METHODS

Study design, cases and controls

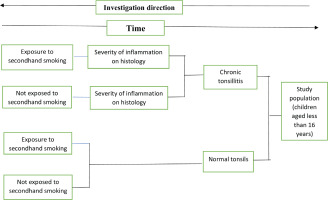

This case-control study was conducted in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery in a tertiary care center in Central Nepal. Children under the age of 16 years diagnosed having chronic recurrent tonsillitis and underwent tonsillectomy between 1 June 2020 and 1 June 2023, were enrolled as cases. Another 150 children without a history of chronic recurrent tonsillitis and having normal tonsils were enrolled as controls. The cases and controls number were the same and all controls were taken from ENT department. The control population visited the hospital for other problems, e.g. ear wax, preauricular sinus and otitis externa. The control population was matched for age and gender. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the College of Medical Sciences, Chitwan, Nepal. A convenience sampling method was used, where children with chronic recurrent tonsillitis planned for tonsillectomy were selected. Chronic recurrent tonsillitis was defined as a minimum of three episodes of recurrent tonsillitis per year for three consecutive years20. Children who were active smokers, on inhaled corticosteroids, or had immunodeficiency disorder were excluded from the study. Data collection was uniform and was done by the principal investigator (PI). History regarding episodes of tonsillitis and exposure to secondhand smoking were taken from patients.

Histopathological examination

After tonsillectomy, the tonsils were sent for histopathological examination. The parameters analyzed in the pathological evaluation were: the grade of inflammation (GOI), the activity of inflammation (AOI), and the hyperplasia (HP). They were scaled as low, medium, or high. Microscopic evaluation with a magnification of 40×0.25 and 20×0.25 was used to count leukocytes, neutrophil granulocytes, and lymph follicles. GOI was analyzed by counting the lymphocytes per ‘high power field’ (HPF) (grades: low <20/HPF, medium=20–40/HPF, high >40/HPF). The grade of fibrosis was also explored (low <1 mm/HPF, medium=1–2 mm/HPF, high>2 mm/HPF) and was considered for the GOI. For the activity of inflammation (AOI), neutrophil granulocytes were quantified (low <10/HPF, medium=10–20/HPF, high>20/HPF). Hyperplasia intensity was quantified using the number of follicles (low <5/HPF, medium=5–10/HPF, high >10/HPF)20. For statistical purposes, 1 point was given for low, 2 points for medium, and 3 points was given for high.

Data collection

The children along with the caregivers were interviewed by PI in the hospital. The interviews included questions on various demographic parameters including age, gender, and a questionnaire of interests such as duration of recurrent sore throat problems, number of episodes of recurrent sore throat in a year, history of secondhand cigarette smoking, number of hours of daily exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke, number of years of exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke, exposure to several cigarettes per day in the home, and exposure to secondhand smoke in public places and at school every week. These questions were asked to both cases and controls (Figure 1).

Assessment of exposure to secondhand smoke

The severity of secondhand cigarette smoking was graded according to the secondhand smoke exposure scale (SHSES). A maximum of 5 points was given to exposure to >20 cigarettes per day, 4 points to 10–20 cigarettes/per day, 3 points to 6–9 cigarettes/per day, 2 points to 1–5 cigarettes/per day, and 0 points to no household exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS). SHS exposure in a vehicle for more than 30 minutes per day was given 3 points, 2 points for those exposed <30 minutes per day, and 0 points for no such exposure. Exposures to SHS in public places and at school were dichotomized (once or more vs never) with a maximum score of 2 points for exposure in public places once or more every week, and 1 point for exposure to SHS in school. Thus, the maximum score of the SHSES was 11 points, while the minimum score was zero21.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics like percentage and mean. For data analysis, McNemar’s odds ratio, logistic regression, Student’s t-test and Pearson correlation coefficient were used. Logistic regression was applied between the main independent variable (secondhand smoke exposure) and the main dependent variable (chronic recurrent tonsillitis patients who have undergone tonsillectomy). The association between the dependent and independent variables was analyzed initially without adjustment for covariates. Later the association of each covariate with dependent and independent variables was analyzed. Then, the covariates were included for adjustment (histopathological score of chronic tonsils, number of cigarette exposure at home per day, exposure to smoke in vehicle, exposure to smoke in school and exposure to smoke in public place) in the multivariable model to determine the association between the dependent and main independent variables. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was done in SPSS version 23.1 (IBM, USA).

RESULTS

A total number of 300 participants (150 cases and 150 controls) were enrolled in the study. In our study, the mean age of all four groups ranged from 10.82 years to 12.04 years (Table 1). Among them, male children were more frequently affected. In the house, the father was a more dominant smoker compared to the mother. Both parents were active smokers in 6 (5.71%) families in the chronic recurrent tonsillitis group and 4 (5.33%) families in children with normal tonsils. The demographic data with the clinical characteristics are given in Supplementary file Table A.

Table 1

Distribution of patients in relation to passive smoking exposure, a case-control study, Nepal (N=300)

| Tonsil status | Passive smoking exposure | Crude OR | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Lower | Upper | |||

| Chronic tonsillitis | 105 | 45 | 2.33 | 1.45 | 3.75 | <0.0001 |

| Normal tonsils | 75 | 75 | ||||

Recurrent throat infections and tonsillar crypt debris were the most common clinical features seen in patients with chronic recurrent tonsillitis (Supplementary file Table B). Among 300 patients enrolled in the study, 180 patients were exposed to secondhand cigarette smoke (Table 1); 150 patients were having chronic recurrent tonsillitis (cases) and the remaining 150 participants were controls. Among 150 cases, 105 children had history of exposure to secondhand smoking at home and the remaining 45 children did not have such history. The odds ratio to find the risk of secondhand cigarette smoke exposure among patients with chronic recurrent tonsillitis and normal tonsils was 2.33 (95% CI: 1.45–3.75, p=0.0005) (Table 1). The ratio was observed to be statistically significant. The p-value was calculated with McNemar’s test with the continuity correction.

An unpaired t-test was done to see the relationship between secondhand smoke score and chronic recurrent tonsillitis. Secondhand smoke scores (SHSS) among cases and controls were compared. As shown in Table 2, the mean value of SHSS of the chronic recurrent tonsillitis group minus control equals 0.87 (95% CI: 0.44–1.29, p<0.0001) pointing towards statistical significance.

Table 2

Comparison of mean secondhand smoke scores in patients with chronic tonsillitis and normal tonsils, a case-control study, Nepal (N=180)

Pearson correlation coefficient (R) was calculated to see any relationship between the duration of cigarette smoking exposure at home and the pathological grade of the tonsils of 105 patients. The value of R as 0.84 (p<0.00001) illustrates a strong positive correlation. Our finding depicts that a higher duration of cigarette smoking exposure is related to higher scores in the histopathological grade of tonsils.

After tonsillar histopathological examination, a score was developed to grade the severity of the infection. This score was compared to various factors responsible for secondhand cigarette smoke (Table 3). Results showed that secondhand cigarette smoke exposure scoring and exposure to smoke in public places correlated with the severity of disease in chronic tonsils. The regression analysis showed that the total pathological infection score was significantly associated with secondhand smoke risk factors (Table 4). The regression analysis demonstrated that if the number of cigarettes exposure at home per day was increased by one unit, the pathological grade of chronic tonsillitis increased by 0.43. This implies that among the four risk factors, the number of cigarettes smoked at home per day and exposure to smoking at school were found to be significantly associated with increased pathological grade of chronic tonsils (Table 5).

Table 3

Correlation of histopathological score of chronic tonsillitis with various elements of secondhand smoke, a case-control study, Nepal (N=105)

Table 4

Analysis of variance of total pathological infection score with secondhand smoke, a case-control study, Nepal (N=105)

| Model | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 141.51 | 4 | 35.38 | 16.19 | <0.0001 |

| Residual | 316.76 | 145 | 2018 | ||

| Total | 458.27 | 149 |

Table 5

Regression analysis of total pathological infection score with secondhand smoke risk factors, a casecontrol study, Nepal (N=105)

DISCUSSION

Palatine tonsils are lymphoid tissue that contribute to various immunological functions22. Among various etiologies for developing recurrent or chronic recurrent tonsillitis, secondhand cigarette smoking is thought as one of the important risk factors. However, there is a dearth of studies illustrating this proposition. This descriptive study explored the effects of secondhand cigarette smoking on the tonsils. Both patients with normal tonsils and chronic recurrent tonsillitis were interviewed regarding a history of secondhand smoking. Histopathological examination of patients who underwent tonsillectomy for chronic recurrent tonsillitis was also carried out to assess the severity of tonsillar tissue damage. Data were analyzed among 150 cases and 150 controls. Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that children with chronic tonsillitis were 2.33 times more prone to have secondhand exposure to smoking at home. The duration of cigarette smoking exposure at home and the pathological grade of the tonsils also showed a strong positive correlation (R=0.83).

Our study aimed to find the effects of secondhand cigarette smoking on lymphoid and non-lymphoid tonsillar compartments by measuring GOI, fibrosis, and AOI. Results delineated that the mean age of children with chronic recurrent tonsillitis exposed to secondhand smoking was 10.82 years. The condition was found to be more prevalent among boys. Though various types of clinical presentations were noted in the children with chronic recurrent tonsillitis, recurrent throat infections and tonsillar crypt debris were the most common presenting features at the first visit. Secondhand cigarette smoke exposure was found as a potential risk factor for chronic recurrent tonsillitis. The severity of the histopathological grade of tonsils showed a positive correlation with both the duration of cigarette smoking exposure and number of cigarettes exposed per day. Regression analysis showed that when the number of cigarettes exposure per day was increased by one unit then the severity of pathological grade of chronic tonsillitis increased by 0.43.

There are few studies evaluating the effects of passive cigarette exposure on tonsils among children. Straight et al.23 showed an odds ratio of 2.49, suggesting that children with chronic recurrent tonsillitis were more than twice more likely to report exposure to secondhand cigarette smoke. A systematic review done by Strachan et al.19 showed inconsistent results about the association between parental smoking and recurrent tonsillitis. Additionally, a study by Said et al.24 showed how parental smoking was related to adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy in children.

According to the World Bank Report 2020, the healthcare expenditure in Nepal in 2020 was US$205.88 per person25. According to findings from the STEPwise Approach to Surveillance (STEPS) survey 2019 in Nepal, around 29% of adults (48% males and 12% females) within the age group of 15–69 years use tobacco products26. Annually tobacco products are responsible for 14.9% (27000) of all total deaths in Nepal27. The number of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) due to effects of secondhand smoking in Nepal was 19.07 (13.58–25.41) for cardiovascular risk, diabetes, kidney diseases, neoplasm, and other non-communicable diseases28. Thus tobacco exposure causes significant health and economic burden to society. Finding tobacco smoke to be detrimental to children, especially resulting in recurrent tonsillitis further focuses on the dark side of tobacco exposure to the pediatric population. Though there are multiple social attempts to discourage the youth from smoking, the dangers of secondhand smoke exposure in the pediatric upper airway, remain insufficiently explored. The findings of this study emphasize the fact that secondhand smoking is responsible for chronic tonsillitis in children contributing to pediatric morbidity and health expenditure. This serves as the primary strength of the study.

Limitations

Though our study is novel in the region, it is a preliminary study and has some limitations. The sample size of this study was small. Only 105 children exposed to cigarette smoking with issues of chronic recurrent tonsillitis were included in the study. Forty-five children with chronic recurrent tonsillitis had no history of secondhand exposure to cigarette smoke. Given that cigarette smoking is a major public health concern, the sample size in this study was small. Moreover, there is the possibility of parents underreporting the children’s exposure to secondhand smoke because of a social taboo and stigma. Social desirability bias and recall bias might have occurred in this case-control study. The presence of residual confounding could not be excluded. Given that all data were obtained from a single, specific location, the findings cannot be generalized to other settings. Instead of self-reported data, a urinary cotinine level could have been used to see nicotine exposure in children29. However, due to financial constraints this method could not be used in our study.

Children are vulnerable to the deleterious effects of secondhand smoking. It is prudent to realize that exposure to secondhand cigarette smoking has been previously associated with recurrent tonsillitis, prolonged recovery, impaired tonsil functions, increased risk of tonsillectomy, post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, and long-term consequences like sleep disturbances, breathing difficulties, impaired growth and development, and increased risk of developing respiratory conditions like asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia30-32. As this was a preliminary study, further studies are needed to establish the relationship between chronic tonsillitis and secondhand smoking.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study illustrates the significant hazards of secondhand smoking on a child’s tonsillar health. Children must be protected from any kind of secondhand smoke. Parents’ awareness and educational tools are needed to ensure better health of growing children to protect them from the detrimental consequences of potentially hazardous effects of passive smoking.